Education, Certification, Compliance: A Day in the Life of a Patient Advocate and Observer

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Recently, I visited a seriously ill, hospitalized friend and colleague. He and I have collaborated on numerous projects in our careers and both of us knew the dangers of spending too much time in a hospital bed. The hand hygiene observed during my 48-hour visit seems all too common and acceptable at many hospitals. The medical staff was very professional, and I admired their responsiveness, care and empathy.

In this discussion, I will focus on the staff hand hygiene and its execution I observed during my visit. Of note, this hospital has an A rating from the Leapfrog Group.

Environment:

• Hand hygiene gel dispensers were deployed outside each room

• A second hand-hygiene gel dispenser was deployed just inside the doorway

• Soap dispenser but no gel dispenser at the sink

• No gel dispenser in the bathroom

Observations:

• Could not validate that each healthcare worker sanitized upon entry

• Some healthcare personnel sanitized upon exit

o Nursing often did “fly-bys,” attempting to sanitize but not properly activating the dispenser

o Physicians were not observed sanitizing upon exit

• Healthcare workers often touched IV station, workstations, etc., but no consequent hand hygiene prior to patient contact

• No hand hygiene prior to donning gloves or after gloves were removed

• Gloved healthcare personnel touched IV station, workstations, etc., without changing gloves prior to touching the patient

• No healthcare personnel used soap/water at the sink

• No environmental services (EVS) visits to perform a room cleaning or a cleaning of high-touch surfaces

• Nursing did not perform a high-touch cleaning

• High-touch cleaning was performed by family and the patient advocate

• Advised by nursing staff that this unit was one of the highest performing regarding hand hygiene.

Clearly, my observations suggested issues with compliance as well as with education and training. It was my impression that the staff were not reluctant to perform hand hygiene, and even welcomed their recognition as a high performing unit. However, as noted above, there appeared to be significant gaps in the staff members’ understanding of appropriate hand hygiene. What education and training could address the observed deficits? Here are some suggestions:

1. Establish and reinforce where and when hand hygiene is required during patient care:

a. WHO 5 Moments (entry/exit is inadequate)

b. Environmental contact prior to patient contact requires hand hygiene, even if hand hygiene occurred at room entry, and much like requirements in the operating room (OR), glove contamination requires re-gloving.

c. Develop a planned workflow: If you touch parts of the environment before patient contact, realize that this will require repeat hand hygiene.

i. Am I going in to adjust the IV pumps?

ii. Am I going to log into the electronic health record (HER)?

iii. Am I going directly to the patient?

iv. Will I be gloving?

2. Establish a high-touch surfaces protocol:

a. High-touch cleaning is required daily.

b. Define who will perform this cleanse, the healthcare worker or EVS personnel

Training/Education/Certification

Clearly, education and training is critical, and the best way to learn is through observation, where errors become valuable teaching opportunities, whether in a simulation center (if available) or observation and training at the bedside. Requiring each staff member to demonstrate knowledge and competence in appropriate hand hygiene during patient care via a practicum each year and consequent certification would assure a well informed and competent staff regarding hand hygiene. Technology can provide significant assistance with observation real time, with electronic monitoring and/or videotaping patient encounters to provide feedback and education as noted above.

Additionally, I would hope that the Leapfrog Group would enhance their survey to include EVS and high-touch surface protocols, just as they enhanced their hand hygiene protocols and guidance over the years.

Exceptional hand hygiene does not just happen and requires investment to support training that results in the outcome we all strive for, reduction in healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs).

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX- The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs. Lee may be reached at: medicaldatamanagement@gmail.com

Why is Exceptional Hand Hygiene Compliance Not More Effective in Reducing HAIs?

By Robert Lee

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Your facility reports hand hygiene compliance of greater than 90 percent, ranked as one of the best by your state for environmental services (EVS), and your Leapfrog Group grades are all As. If this is your integrated delivery network (IDN) or hospital, one might ask why patients continue to acquire an infection during and after their visit to your hospital. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports, “Each day, approximately 1 in 31 U.S. patients and 1 in 43 nursing home residents contracts at least one infection in association with their healthcare, underscoring the need for improvements in patient care practices in U.S. healthcare facilities. While much progress has been made, more needs to be done to prevent healthcare-associated infections in a variety of settings.”1

Fast forward to 2023 and the post-COVID era, where rather than a decrease, there was an increase in HAIs last year despite our intense focus on universal precautions. Is hand hygiene compliance, environmental cleaning, and other interventions ineffective or is reporting inaccurate?

Focusing on hand hygiene compliance, the CDC reported that the average hand hygiene compliance in the U.S. is less than 40 percent.2 The goal of hand hygiene is to eliminate or greatly decrease microorganisms on hands and thereby prevent or significantly decrease the transmission of these potential pathogens to patients. If hand hygiene is performed before entering a patient’s room and soon after there is hand contact with a cell phone, tablet, bedrails, etc., hands can become colonized with microorganisms present on those other surfaces, and, of course, potentially spread those organisms to the patient if no hand hygiene is performed in the interval before patient contact.

Clack, et al. (2017) found that hospital personnel contaminated their hands by touching surfaces in the patients’ room within 4.5 seconds post entry.3 Therefore, even though compliant with hand hygiene prior to room entry, contamination occurred during non-patient environmental contact prior to patient contact. Returning to the preceding discussion, if your institution’s hand hygiene compliance score is 99 percent but you have environmental contact soon after entering the room before patient contact, what is the efficacy of such exceptional compliance in infection prevention? Consider behavior in the operating room; if anyone on the surgical team contaminates their gloved hands, an immediate glove change is required before any further contact with the patient, sterile instruments, or the surgical field. In surgery, hand hygiene guidelines are strictly enforced even after entering the patient’s space, in contrast to the behavior that often occurs in other patient-care areas.

What steps can be taken to adjust to this data and prevent hand contamination prior to patient contact? One obvious consideration in measuring hand hygiene compliance at the point of care (POC) rather than the doorway. Adding dispensers inside the room and improving training to change behavior to be more consistent with what occurs in the operating room where any break in technique requires re-gloving at a minimum would be a start. A torn or damaged glove in the OR requires repeat hand cleansing and re-gloving; the same approach to regular patient care would move us closer to more effective hand hygiene where it really matters (POC) and potentially enhance the outcome of all these efforts, a decrease in HAIs and improved patient outcomes and care.

Of course, this is not the only intervention or factor impacting HAI, but one of the factors within our control. Other considerations to enhance infection prevention include high compliance with environmental cleaning and disinfection, visitor and patient hand hygiene compliance, and controlling antibiotic use, etc. No single intervention alone is appropriate but rather, as noted by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), a global and “horizontal” approach to the infection prevention interventions is within our control to achieve the ultimate outcome, reducing HAI.4

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs. Lee may be reached at: medicaldatamanagement@gmail.com

References:

1. CDC HAI Progress Report. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/progress-report.html

2. CDC Hand Hygiene Core Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/download/hand_hygiene_core.pdf

3. Clack L, Scotoni M, Wolfensberger A, Sax H. "First-person view" of pathogen transmission and hand hygiene - use of a new head-mounted video capture and coding tool. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017 Oct 30;6:108. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0267-z. PMID: 29093812; PMCID: PMC5661930.

4. Septimus E, MD, Weinstein RA, Perl TM, Goldmann DA and Yokoe DS. Commentary: Approaches for Preventing Healthcare-Associated Infections: Go Long or Go Wide? Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiol. Vol. 35, No. 7, July 2014.

How Important is Hand Hygiene in the Use of Gloves, Masks, Surgical Drapes and Gowns, and other Medical Devices?

By Robert Lee

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Infection prevention is not a singular intervention; as Septimus, et al. (2014) note, multiple interventions implemented simultaneously is recommended. And as Wohrley and Bartlett (2018) observe, “Horizontal strategies seek to broadly reduce the burden of common healthcare-associated pathogens including S. aureus, Enterococcus, gram-negative bacteria, and Candida through interventions such as hand hygiene and environmental cleaning.”

As a result, it is very difficult to determine the cause and effect of each intervention. We know that hand hygiene is a key component, but high levels of hand hygiene compliance do not always result in infection rate reduction. Why?

In this article, I consider the relationship between hand hygiene and medical devices such as gloves, masks, surgical drapes/gowns, etc., as well as explore how this relationship reduces or accelerates the risk of infection transmission.

Gloves

Why do you wear gloves and when do you perform hand hygiene? According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), “Use medical gloves when your hands may touch someone else's body fluids (such as blood, respiratory secretions, vomit, urine, or feces), certain hazardous drugs or some potentially contaminated items. Hand hygiene should be performed prior to and after removing gloves. Unfortunately, gloving has been used as a substitute for hand hygiene. Gloving protects the wearer, but improper glove use can result in pathogen transmission from patient to patient, patient to surfaces, etc. When reminding staff on how to use this medical device, many acknowledge and are appreciative, but an alarming number demonstrate that their only concern is their own protection.”

Masks

So, did you know that masking can both help prevent transmission of microorganisms or can accelerate the transmission of such organisms? You must ask which microorganism/pathogens you are trying to address. Is it viral or bacterial? Most masks are designed for bacterial not viral protection. Unless you are using a sheet of plastic, viruses will permeate your mask. Bacteria and viruses use vehicles such as liquid, moisture, particulate matter, blood, bodily fluids, even airborne dust, as well as hand contact, etc. So, if you are trying to prevent viral transmission, as in SARS-COV-2, and you are not sanitizing your hands, touching your face, your cell phone, and your mask, then you may be risking viral contamination. We are told to wear masks, but we are not told how to use this medical device properly. Thus, this can contribute to increased transmission. You must ask yourself, why are we not being told how to properly use masks if they are so effective in reducing the risk of catching and spreading a viral pathogen?

Evidence-based studies show the average individual touches his or her face 23 times per hour (Kwok, et al., 2015). Tajouri, et al, (2021) showed that 45 percent of cell phones carried SARS-CoV-2 during the pandemic. Do you think that individuals performed proper hand hygiene each time they touched their faces or handled their cell phone? Of course not. Think of a couple of common scenarios. How about your children at school who were required to mask, usually with a single mask worn all day. How about members of the public in a grocery store wearing masks and gloves, touching everything in sight and never doing hand hygiene? Watch television and you’ll see public officials or other personalities who are wearing and touching their masks but never doing hand hygiene.

Drapes and Gowns

Over the past 30 years, surgery has demonstrated the importance of barrier material and the science of sterile technique. The same principles as articulated above apply, but the difference in the operating room (OR) is that OR personnel revisit these principles during each case. They also hold each other accountable for maintaining proper technique. Surgical drapes and gowns are manufactured with the knowledge that fluid, blood, particulate matter, and touch are all vehicles for pathogen transmission. Drape and gown technology is focused on fluid penetration barrier performance while balancing comfort and drapeability. Materials are either permeable or impermeable; performance is matched to the expected opportunity for them to encounter blood, fluid, or particulate matter, as well as taking into consideration the length of case, risk of foreign bodies, etc. Even with all this technology, hand hygiene and hand hygiene science are important parts of the sterile process. Should hands become contaminated (usually gloved), rescrubbing may be required and/or re-gloving. Nevertheless, in the OR the hands play a pivotal role in the infection prevention chain.

So, considering the above scenarios, what should we take away from this article?

1. Use your critical thinking skills. Consider both sides of the equation, what is said and what is not said.

2. Understand the science and follow the science. Understand microorganisms and their mode of transmission.

3. Use your common-sense logic.

4. Audit your personal behavior and apply these principles of science and logic.

5. Come to your own conclusions. Don’t blindly accept what is pushed on you by the media.

I ask the question that if hand hygiene is the No. 1 way to reduce the risk of infection, why do we not get the correct guidance on how and, most importantly, when to perform hand hygiene? Additionally, with so many vehicles and modes of transmission of pathogens (cell phones, masks, etc.) with hands at the center, why are we not educated and made aware of how, when, and why hand hygiene is as important, if not more important, than using this medical device (masks, gloves, etc.)?

I am not against the use of any of these medical devices if they are used properly, training and education is provided (how to use and how not to use) and are supported by evidence-based research. Anything short of this I view as medical malpractice. We have been seriously uninformed for whatever reason and, as individuals, we have not assumed our responsibility to use our critical thinking skills to arrive at the proper conclusions. This lack of critical thinking has resulted in the loss of thousands of lives; many who might have been our own loved ones. So, put on your thinking cap and let the science, data and common sense set you free and maybe save your life.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX- The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs. He may be reached at: medicaldatamanagement@gmail.com

References:

Septimus E, Weinstein RA, Perl TM, Goldmann DA, Yokoe DS. Approaches for preventing healthcare-associated infections: go long or go wide? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Sep:35 Suppl 2:S10-4. doi: 10.1017/s0899823x00193808.

Wohrley JD and Bartlett AH. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Children. Springer Nature. Published online July 16, 2018; 17-36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-98122-2_2

Kwok YLA, Gralton J, McLaws M-L, et al. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2015 Feb;43(2):112-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015.

Tajouri L, Campos M, Olsen M, et al. The role of mobile phones as a possible pathway for pathogen movement, a cross-sectional microbial analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021 Sep-Oct;43:102095. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102095. Epub 2021 Jun 9. PMID: 34116242.

Integrated Delivery Networks and Hand Hygiene Compliance

By Robert Lee

This article originally appeared in the December 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

A healthcare Integrated Delivery Network (IDN) is an assemblage of healthcare providers, including both acute (hospitals) and non-acute care sites (clinics, physician offices, surgery centers, long term care, etc). Supply chain systems and processes used in an acute-care hospital are not always effective in the non-acute care setting. Technology, workflow, supplies, information technology, data and skillsets of personnel can differ significantly. Two things are common to both sides of this equation, however: cost and quality/safety (infection prevention).

A question to consider is why? Within an IDN (and even within individual hospitals) are there various tiers of acuity and compliance with hand hygiene compliance? Why are rules, or at least compliance with accepted standards, different for downstream (non-acute care) and upstream sites (acute-care sites)? Even within an acute care setting, rules and/or compliance may vary among different departments, such as the OR, OB, MedSurg and ICU. Assessing the differences in these individual departments would be an interesting exercise as, if infection prevention is everyone’s responsibility, one would expect the entire IDN to be consistent across all departments regarding infection prevention.

Observations during several consulting engagements assessing hand hygiene compliance provided some insight into these issues. In one setting, the staff was observed working during patient care, both from different sites on the ward as well as during patient-to-patient care. Gloves were commonly employed but often there was no hand hygiene performed during glove changes and often less-than-ideal hand hygiene compliance. At a second major IDN in the central United States, physician, staff and patient-care workflow were assessed in an ambulatory setting. Hand hygiene technology was employed to track workflow during patient care for seven days, employing smart dispensers and smart ID badges to track hand hygiene compliance. The engagement resulted in restructuring of patient-care flow, but hand hygiene compliance for this 25-exam room physician clinic was less than 10 percent. At a large teaching hospital in the Southeast, our team measured hand hygiene compliance in the perioperative space. Despite the unit’s location contiguous to the OR, where hand hygiene and sterile technique are maximized, hand hygiene compliance was less than 17 percent. Finally, at a large IDN in the Southeast, consultation was requested to identify gaps in quality, focused on improving hand hygiene compliance and Leapfrog Group scores. The initial assessment suggested that this IDN would spend $100 million over the next five years to service their infections.

Returning to the question posed previously, why do the rules and compliance seem to differ upstream, downstream and inter-departmentally? To decrease healthcare-associated infection (HAI), there should be consistency in hand hygiene goals, performance and outcome (compliance) to decrease the morbidity, mortality and cost associated with HAIs. To reach these metrics there must be careful assessment of the differences upstream and downstream, as well as within individual departments in a single site. With this data, to enhance outcomes, there must be consideration of how we train, educate, and maintain appropriate and maximized hand hygiene compliance. Are our current rules and guidance sufficiently rigorous? One consideration is to develop a training program where all personnel are certified each year via classroom, on the job and, where available, simulation training, the last approach the most effective mode to demonstrate in actual practice the skills critical to effective hand hygiene, to protect both patients and personnel and decrease HAI. Finally, IDNs need to standardize both upstream and downstream infection control guidelines and expected, as well as appropriately assessed and documented, compliance in this important patient and staff safety protocol.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Are Supply Chain Executives Missing an Opportunity to Impact Patient and Staff Safety and Efficiencies?

By Robert Lee

This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

When I meet with supply chain executives and their staff, I often receive questions such as, “Can you save us some money?” “Can you do some analysis on our current product mix and show us lower cost alternatives?” The answers to these questions are “Yes” and “Yes.” However, members of the supply chain must have a broader scope of cost reduction. Supply chain is the gateway to ideas, just as the emergency room and operating room are the gateways to initial patient interactions with that institution.

Is this your supply chain?

Model A

Model B

The modern supply chain organization has to be structured like Model B and led by executives who understand the holistic approach to this important resource. At the core of this model are the three C’s: Collaboration, Communication, and Creativity. We all know that collaboration and communication are key to a matrixed workflow, but why creativity? The supply chain executive must lead by example and encourage out-of-the box thinking and ideas on value to the organization and not just be focused on price. The evolution of the supply chain executive goes well beyond cost savings from contract analysis and implementation of more cost-effective contract options. The opportunity is being the organizational leader who finds, evaluates, and presents pragmatic solutions to senior executives that go well past product conversion and implementation.

The role requires a holistic approach that views the patient’s and the organization’s continuum of care. The view should be that what is best for the patient is congruent with what is best for the organization. For example, if there is a new surgical device that cost more but results in better outcomes (such as reduced length of stay, reduced number of infections, reduced procedure time, etc.), instead of the singular focus on the cost of the device; instead, the total impact of the device’s use presents a patient and financial benefit. To get at the overall analysis for the organization, it will require engagement with the various stakeholders in establishing metrics, tracking outcomes, and making sure results are validated. It requires assuming the role of the leader who presents to the organization opportunities that have been formulated with the key stakeholders, who will also be part of the initiative’s success.

So, let me present an idea that supply chain executives and their teams should investigate and why. The topic is systemwide hand hygiene compliance and surface decontamination. Current evidence-based studies (proprietary) indicate a 50 percent reduction in infections when an automated hand hygiene compliance technology is implemented. Additionally, evidence-based studies (yet to be published) around surface/room decontamination indicate almost a 99.9 percent reduction in contamination. Do you know what your facility infection rate is and the cost to service these? Working with data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and an integrated delivery network (IDN), it was determined that this IDN would spend $100 million over the next five years to service their current infections. By the way, the CMS data is only what has been reported, and this number could be higher.

So, here are some takeaways:

1. Are supply chains focused on the appropriate metrics?

2. Are supply chains structured to support other issues beyond cost alone?

3. How does your supply chain approach value analysis?

Is your supply chain just a purchasing group or is it a strategic resource that impacts both top-line revenue and bottom-line expense, while improving quality and safety for staff and patients?

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Prevention as Our First Line of Defense With Hand Hygiene as a Top Priority

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

With 99,000 deaths in the acute-care space annually and 400,000 deaths in non-acute space according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one would think that with all the interventions employed during the COVID-19 pandemic that we might see the needle move on these metrics.

We are under assault each day as organisms continue to evolve and adapt; some friendly and some not so friendly (pathogenic). We have become such a pill-focused society that much of our focus has been on pharmaceuticals and vaccines. So, why are our priorities reversed? Granted, prevention is not sexy, easy, and as profitable as a new drug (usually +95 percent margins), but prevention is unique in that it is universal to all microorganisms, non-specific, broad in scope, effective against all microbes (viral or bacterial), no side effects, and no profit margins or incentives except patient and staff safety.

One of the major reasons why prevention takes a back seat to pills is that it is a complicated, collaborative process. In speaking with infection preventionists they say, “It’s like herding cats.” I like to make the comparison of the job of infection prevention, particularly prevention, to going to the moon and to that famous quotation: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” (JFK Library.org)

So, how do we prioritize prevention as the first line of defense and our top priority?

- Understand and align goals with the organization

- If patient and staff safety is a top priority, you will need to align and convince the powers that “prevention is the first line of defense”

- Research the tools /solutions that will help you accomplish your mission and accommodate your organization’s needs

- Understand tools you will need and what you want to measure

- This will require researching the commercial landscape of vendors and providers

- Put together a short list of your choices

- Remember not all technologies, platforms, etc. are created equal

- Do your homework: ROI, performance indicators (KPIs), metrics

- Preparing a strategy, both financial and operational, with measurable and achievable metrics.

- You need to measure what you plan to manage.

- Value proposition: Roadmap of how you going to get there

- Gather all your data, documentation, studies, etc. and organize into your narrative

- Make sure you support with current “evidenced based” studies for many studies lack credibility due to age.

- Prepare your presentation/pitch deck

- Pick your team of collaborators; what is in it for them?

- You want to surround yourself with Teammates that are passionate about your mission

- What’s in it for each one? Is there both a personal and Team gain?

- Make sure you surround yourself with good communicators that can articulate the goals and process.

- Seek an administrative sponsor/coach

- Find your executive sponsor.

- Generally, the chief quality officer, chief nursing officer, chief financial officer, chief information officer, etc.

If you have done all the above, you are now ready to execute on your plan. You will want to seek the help of your healthcare value analysis department or supply chain team to assist you in the RFP/bid/procurement process.

We will not cover the implementation portion here, for the intent of this article was to help you to prioritize prevention as the first line of defense in your infection prevention strategy. If you have any questions or needs, you can always reach out to me directly at: medicaldatamanagement@gmail.com.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene Data, Analytics and AI: What is Your Strategy?

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

As hockey legend Wayne Gretzky says, “I don’t skate where the puck is, I skate to where the puck is going to be.” Knowing where the puck is going to be takes a bit of calculation, direction, speed, relative movement, weight of the puck, condition of the ice, etc. These are all data points that when processed provide an expected proximity and location for the puck. Bad data, tardy information, and lack of robustness will lead us in the wrong direction.

What role does analytics and near real-time data play in allowing us to target key activities that we know have a real effect on quality, safety and can impact healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs)? And how is this data presented and used by your management team to help to improve performance?

Before you get to the analytics and reporting, it is important to have a robust, accurate, and efficient “data capture” solution. The adage, “Garbage in garbage out” is so true. Typically, the gathering of hand hygiene compliance data can be manually collected on a clipboard. Some will use an iPad. Nevertheless, a manual input of data is required, which can open the door to errors and inefficiencies. Additionally, the scope of data is very limited to this human resource. The Leapfrog Group recommends that at least 200 events be captured to meet their survey requirements per unit.

One way to multiply your data gathering task is to use hand hygiene technology. This standardizes and accelerates the data-gathering process and can provide more accurate results in a fraction of the time. Some technologies require permanent installation, while others are “portable” and can be installed, de-installed, and re-deployed in a few hours, moving from unit to unit. Additionally, The Leapfrog Group recommends that you validate the performance of your tool via audit each time you install/de-install.

So, once you are comfortable with your data-gathering process, it is time to put the data to work and into the analytics platform, which organizes, sorts and prepares the data for reporting.

So, how do you want your management team and end users to receive their reports? Should it be via email, text message, or through a dashboard? Should it be delivered weekly, daily, or near real-time? How do you want to use this reporting functionality? To track performance, for training and education purposes, to document operational and clinical health of the team, or to track as it relates to infection rates?

As far as analytics, determining trends and relationships is an important function used to become more predictive versus retrospective. We want our data to move faster than the process itself so that we can anticipate appropriate interventions and take preventive measures. We might want to know the relationship in hand hygiene between nurses and doctors, other clinical service staff such as environmental services or dietary, and others such as visitors. This might include different shifts, weekends versus weekdays, duration of shifts, etc.

What is artificial intelligence (AI) and how does it apply to hand hygiene? AI is simply taking all this good data and analytics and providing additional direction as an output. It’s called machine learning. The information is stored and managed in such a way that it allows the AI platform to think ahead as to next steps and activities. It allows us to become more predictive, which is one of our goals. While in today’s healthcare setting, many clinicians are working tirelessly with fewer resources, in the old days, nurses use to work in teams called “the buddy system.” Technology is an important part of “the buddy system,” especially when there is no back-up resource to ensure quality and safety. When trying to achieve high performance and compliance with safety protocols such as hand hygiene, wouldn’t it make sense to have a technology assistant reminding you when to sanitize your hands? It might be an audible, visual, or a voice reminder.

Do you subscribe to the “command center” concept? This concept is a live/real-time dashboard of hospital health and quality. Does your compliance data feed into your electronic health record (EHR)? Every infection prevention office or department should have a real-time feed (command center), broken down by hospital, department, and unit, with drill-down capabilities to individuals.

If we are going to ask our staff to do more with less, does it not make sense to invest in assistance that makes them better? One should not fear “Big Data” or AI; it is your friend and ensures that you are doing the right things at the right time.

Epidemiology and infection prevention need and deserve the opportunity to bring practice into the 21st century. Clinicians deserve access to resources and funding to help them fight hospital infections and antibiotic resistance. Data is the new currency in the marketplace, and clinicians need to access that information efficiently, accurately, and in real-time. Administrators, please support your epidemiology and infection prevention teams when they ask for funding and resources.

Robert Lee, BA, CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX-The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene: Visitor Hand Hygiene Compliance and the Infection Prevention Chain

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

A common refrain pertinent to the infection prevention chain is that each segment is only as strong as the weakest link. Pathogens spread through the hospital ecosystem via carriers, most commonly hospital personnel and patients, and hands are the most common vector of transfer. A major component of the infection prevention chain is the education and training of staff and recently the investment in technology to sustain and improve hand hygiene compliance. However, another important potential link in the infection prevention chain is the transfer of pathogens by visitors, often given inadequate consideration.

In my anecdotal experience visiting hospitals, visitor hand hygiene is seldom if ever a consistent focus of infection prevention programs. Pitts, et al. noted that staff hand hygiene compliance is generally 25 percent to 40 percent while visitor hand hygiene is usually less than 1 percent. A recent study by Kaya, et al., noted: “Of patient companions and visitors, 96.2 percent stated that they did not receive training on the importance of handwashing during their stay in the hospital.”

Several investigators have addressed some of the issues surrounding visitor hand hygiene and the challenges that result in such low hand hygiene compliance. Hobbs, et al. noted the lack of placement of hand sanitizer dispensers where visitors commonly enter the hospital, typically the front door of the hospital. Further, hand sanitizing displays in the hospital entrance alone would help raise overall visitor hand hygiene awareness and knowledge of its importance and potentially increase visitor compliance. Visitors (and often patients) receive little if any education and training in hand hygiene, such as the why, how and when.

What might be some practical options to address some of these challenges?

A common requirement for all visitors entering the hospital patient-care area is to secure an identity badge as they pass through security. What if part of this process was to require new visitors to watch a brief one-minute video addressing the importance of hand hygiene? Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic raised the issue of the importance of prevention of pathogen transmission among members of the general public. Further, most visitors to the hospital are coming to see friends and family, and preventing infection could and should be an important aspect of such visits. It seems an unrealistic expectation of visitors to understand the importance of hand hygiene without providing appropriate information and the means to address the problem, as noted above.

They then can take this certification to security check in and receive permission to enter the hospital. If the hospital is a subscriber to hand hygiene technology, visitors could at that time receive a hand hygiene compliance ID badge. This badge will remind them when to sanitize their hands. Additionally, it will provide tracking information and contact tracing should these features be necessary.

This process is a start, an opportunity to address one weakness in the chain of infection prevention, seldom currently a high priority at most hospitals. It is an opportunity to both provide visitors with the knowledge of the importance of hand hygiene in infection prevention and hopefully easy access to hand hygiene before visitation. If current visitor compliance is truly less than 1 percent, there is really only one way to go.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Moving Hand Hygiene-Product Dispensers Closer to the Point-of-Care

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

As we continue to work with our clients, the most common reasons noted regarding the challenge of lower-than-expected hand hygiene compliance are hand sanitizing dispensers not being available, lacking easy access, being empty, being non-functional, and not dispensing the correct amount of sanitizer. This is a universal problem that needs to be understood and addressed.

The first two dispenser-related challenges noted above question the logistics and placement of sanitizer dispensers. In terms of these issues, there is one question to consider: Is your sanitizing dispenser footprint designed on entry/exit or the World Health Organization (WHO) Five Moments protocol? Some programs are employing the Five Moments protocol, but their dispenser footprint is entry/exit, where dispensers are set at the doorway and the sink area.

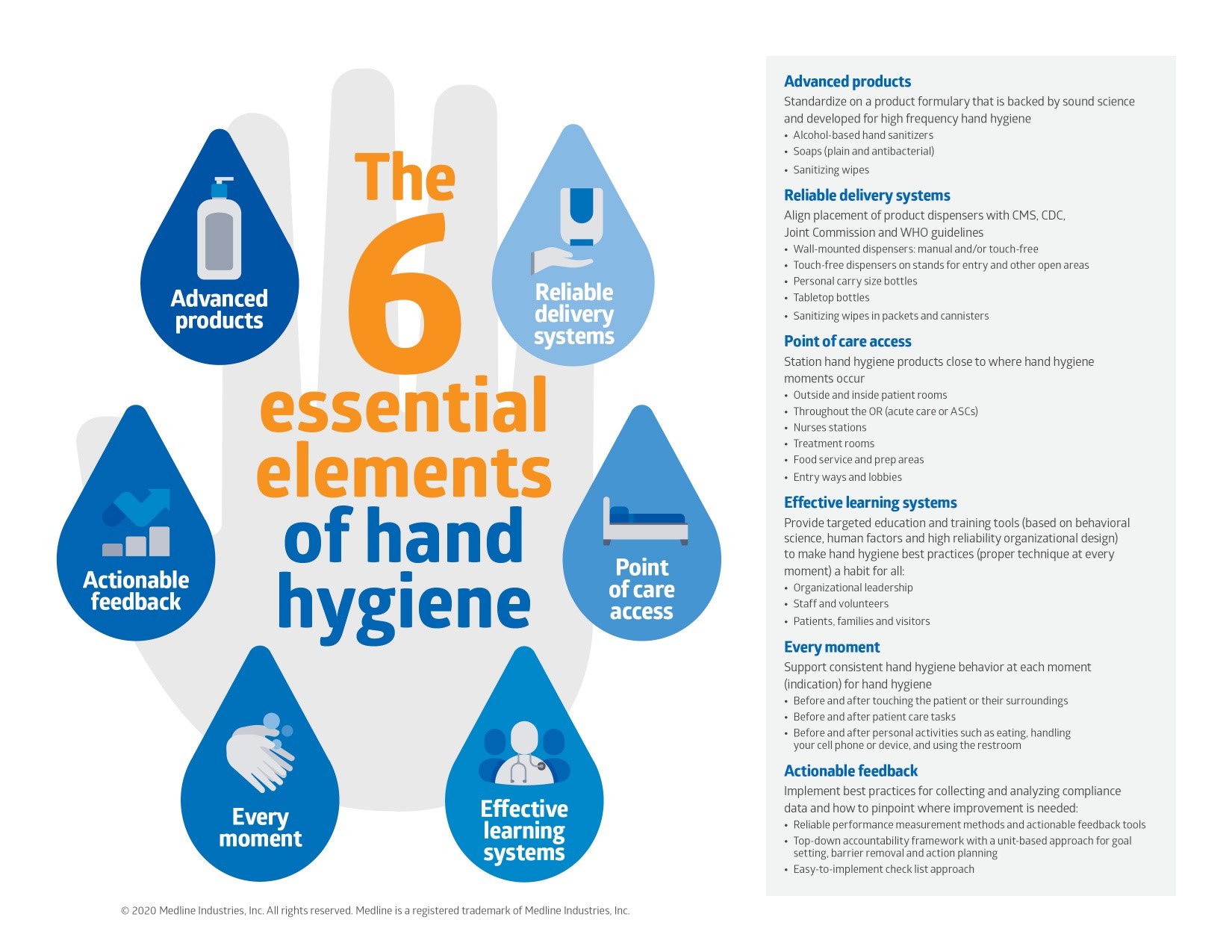

A WHO 5 Moments dispenser workflow design would place dispensers at the sites indicated in blue in Figure 1 below.

Moving the dispensers closer to the point of care (POC) makes it easier for staff to sanitize hands and eliminate unnecessary steps, as 70 percent of all hand hygiene opportunities occur inside the patient room, studies have found. Consider asking your vendor to add additional dispenser sites, as these dispensers are no-charge items.

The third, fourth and fifth dispenser-related challenges mentioned earlier are a consequence of inadequate maintenance and servicing of your dispenser platform. If this is an issue, an important consideration is your method of maintaining your dispenser’s function and solution supply. One approach is manual, where hospital staff (typically environmental services personnel are the most commonly responsible professionals for this task) check each unit or, in some units, the unit team checks prior to shift change or the charge nurse is responsible for validating the sanitizer platform.

Can technology play a role? Many hospitals are beginning to employ hand hygiene technology to measure hand hygiene compliance. A byproduct of this technology is the assessment and maintenance of “smart” hand hygiene dispensers. Each dispenser records the number of times that it is activated and alerts staff when a solution refill is necessary. It also identifies dispensers that are inoperative and require attention and potentially repair. Considering the critical importance of dispenser function for effective, compliant hand hygiene, technology may be a viable solution to compliance and maintenance issues.

It’s all about the data. What kind of good data and insight can be gained? What do analytics tell us?

Firstly, you must measure the right thing. If your footprint is set up around entry/exit, that is what you are measuring. So, what happens though once you enter the room? If you set your footprint to measure the WHO 5 Moments, then your metrics and analytics will provide you with more granular data and a more exact measurement of your hand hygiene compliance, patient room health and your sanitizing station readiness.

Remember, data is the new currency in the marketplace; as W. Edwards Deming has said, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

So, in this article we have addressed some ideas that will not only enhance your current hand hygiene compliance, the acceptance of your efforts to improve performance, your dispenser service and maintenance, but also to help you to convert from entry/exit to the WHO 5 Moments methodology.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX -The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene and Surfaces: The Case for Big Data, Lean 6-Sigma and Improved Standardized Training and Education

by Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Hand hygiene is not handwashing but rather the execution of cleaning and sanitizing one’s hands properly at critical times during patient care. Unfortunately, achieving this goal at a high level of compliance has proven difficult. Sanitizing your hands upon entering a patient’s room and then using the keyboard of a workstation, handling a patient chart, or touching anything in the room prior to touching the patient can negate the impact of hand sanitization and potentially acquire a pathogen that can then be transferred to the patient during contact. Entering a room and quickly activating a dispenser but never ensuring that a proper amount of sanitizer is dispensed and that the dispensed solution is properly dispersed and spread over the surface of the hands can also negate the value of hand sanitization.

Part 1: Sanitizing Your Hands

Guidelines for appropriate hand hygiene are widely available and an important component of infection control training and reinforcement. Recently, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) published some newer guidance focused on fingernails, polish, fingertips and maintaining healthy skin (Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2023, 1-22). Because healthcare personnel average about 200 hand-hygiene opportunities per shift, compliance and proficiency are critical and challenging. Sanitizing hands this many times per shift can cause skin damage which can both impact compliance and increase colonization with potential transferable pathogens.

Part 2: When Should I Sanitize My Hands?

The question I would like to ask is, “If your child, parent, grandparent, or significant other happened to be flying on an airplane today, and you were told that airplane conformed to the minimal standards of safety and airworthiness, would you let your family fly on the aircraft?” The point I am trying to make is that the standards established by organizations are minimal standards of performance, not maximum standards.

The traditional minimal standard of timely hand hygiene sanitization is the concept of entry/exit, or sanitizing hands upon entry to or exit from a patient room. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined the minimal standard of hand hygiene centered on the 5 Moments (See illustration). This approach adds other instances requiring hand hygiene, such as contact with equipment or surfaces in the patients’ environment. The recognition of potential contamination “beyond the doorway” addresses the issue of hand contamination after hand hygiene prior to entering the room and subsequent contamination of previously sanitized hands with potential pathogens when touching surfaces in the patient rooms. Although this expands the need for hand hygiene in new situations, it also offers a more effective method to avoid transfer of potential pathogens in the patient care environment.

Part 3: Process Improvement

Pathogens don’t have legs but we give them legs, as our hands and surfaces provide mobility for pathogens. A critical component to address the issue outlined above is a performance improvement team. Enhancing your infection prevention and control program and potentially moving to the 5 Moments guidelines should precipitate engagement with Lean 6 Sigma to assist your endeavors. You should engage them to provide Lean 6 Sigma for the unit that you hope to implement your hand hygiene compliance strategies. Collect good data on current state and project your future state by applying “lean principles” to your unit (lean process) and eliminate any opportunities for error (6 Sigma).

Now you can establish the proper hand hygiene protocol for that unit. You can also train staff on what are the scenarios that require hand hygiene and when. An example might be:

1. Sanitize hands upon room entry

2. Approach the workstation and enter patient information

3. Sanitize upon leaving workstation and prior to patient contact

4. If there is patient contact, sanitize after touching the patient and before touching anything else.

5. If leaving the patient, sanitize upon exit from the room

Note: Hand hygiene is performed when interaction between surfaces and patient, patient and surfaces, and surfaces and surfaces.

Now you can train and educate staff members on that unit. With the workflow standardized to a point, one can easily teach and educate the staff on when, where and how to practice hand hygiene. You will also know exactly what you are measuring, and compliance data will be much more accurate and meaningful. Of course, there will be exceptions, as patients come first. Muscle memory and habit will improve over time when hand hygiene is defined effectively to match the standardized training and education process.

To summarize, each unit workflow is different. Before you begin to measure hand hygiene compliance, you must understand your workflow. Where do your key hand hygiene opportunities exist? Gather this data with your team and establish standardized protocols. Then overlay a compliance measuring tool. Use this data to improve performance. Remember, each unit has a unique workflow unless you standardize universally.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX- The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene Compliance Monitoring Technology: Buy, Lease, Outsource, SaaS … What’s Right for You?

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Why are infection prevention and environmental services departments the last place where hospital administrators want to spend money? Why must infection preventionists (IPs) utilize clipboards, spreadsheets, volunteers, poorly trained observers, and a manual methodology to monitor hand hygiene, the most effective method to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and protect patients?

This discussion is designed to help IPs evaluate the technological choices available to address hand hygiene monitoring as an alternative to the manual method. Important considerations include current challenges to more effectively address the requirements of hand hygiene compliance and your institution’s situation and objectives. Choices include purchase, lease, outsource or continue your current program.

Here are some of the questions to consider:

1. What is your institution trying to accomplish and what type of help/resources are necessary to meet your goals?

2. Is your approach to create your own system or purchase a proprietary system?

3. If your goal is to create your own system, how will you design, implement and maintain it?

4. If you decide to purchase a system, will you buy, lease, outsource, or other (software as a service or SaaS)?

The Purchase Option

This is the most straightforward approach. Each system component has a cost and sell price, and, depending on the system, potentially a distribution cost. Each system will vary in price, depending on your footprint design. It is therefore critical to understand your hand hygiene compliance footprint, meaning what you want to measure and what you want to achieve. The hand hygiene compliance footprint is a designed workflow that is mapped as well as standardized to efficient workflow and hand hygiene protocols. (The choice and design of an appropriate footprint will be considered in a future column.)

Once you have itemized the parts, you need to consider other costs:

• Service costs, including parts and maintenance, warranty and customer support

• Lost, damage and theft

• Technology upgrades

• Installation and de-installation

• Additional consulting

When you choose to purchase, you own the technology and it is considered a capital expense, usually considered and procured through the capital expense process; this is usually a competitive process among different departments with the performance of a needs assessment.

Leasing Hand Hygiene Technology

Leasing is another consideration, which is essentially renting the technology for a period of time at a specific rate. Leasing can include a lease-to-buy scenario, where a portion of your lease payments are allocated to the purchase of the technology. Leasing helps to avoid the capital expense process, as leases are generally allocated to operating expense as an ongoing cost. Additionally, all the other costs noted above are operating expenses.

Leasing may be a practical choice to avoid competition for capital, lock in a fixed term of service, potentially accrue equity in the technology, and upgrade or change the technology in the future.

Outsourcing Hand Hygiene Technology

You may also consider a software as a service (SaaS) model. In this model you neither purchase nor lease the technology but choose a company to provide complete access to hand hygiene compliance services for a fee.

A SaaS model for hand hygiene technology provides all the benefits of leasing, as your firmware and software are updated automatically and seamlessly, and all the other service features of a lease agreement are included. With the current rapid development of new technology and needed software updates, SaaS agreements are the current standard. Whatever approach chosen when adding a technological approach to a hand hygiene program, a cloud-based platform is essential, as hand hygiene technology is so data intensive, it requires each individual sensor station to communicate efficiently, accurately and instantly.

In summary, depending on the size and resources of your institution, there are several business approaches to the acquisition of hand hygiene technology. A smaller hospital where the infection prevention department comprises a single person, technology enhances the ability to collect robust, performs 24/7, is a force multiplier for IPs, and may make clinical and economic sense. In large integrated delivery networks (IDNs), technology allows IP to target their influence and enhance teaching and education, rather than collecting and analyzing data that is more effectively and efficiently collected via technology.

A final consideration is to engage a vendor in a risk/share/gain agreement. Such agreements can align your goals and metrics with the supplier and provider, a means to pay for your hand hygiene technology, as well as provide an ROI and expense reduction for your system.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene and Surfaces: Are Your Education and Training Efforts Doing Enough to Move the Needle on HAIs?

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Could your training and education be doing enough to support your integrated, collaborative approach? Let’s look at your current state first and then we can explore some ideas to consider.

In the military we always say, “You train as you fight.” In coaching, we say, “You practice like you play.” We are in a battle with pathogens, the unseen enemy, and don’t seem to apply the same principles, techniques and resources necessary to win the battle. What did we witness with COVID-19?

In a previous columns we spoke about both vertical and horizontal approaches to addressing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). The vertical approach attempts to identify the pathogen and then to implement treatment for that pathogen. A horizontal approach addresses infection on a more broad, non-specific approach where interventions do not target a specific pathogen. Vertical is more tactical and horizontal is more strategic. With this article, we will attempt to illuminate an important horizontal approach, education and training, which is so important, but apparently severely under-resourced, in need of re-thinking and requiring your utmost attention.

In a recent survey conducted by our organization, we asked the following questions to hospital personnel:

1. How important is hand hygiene to patient safety and staff safety?

2. Do you know your current hand hygiene compliance?

3. Is it based on the WHO or CDC minimum standard?

4. What is the difference between OR sterile technique principles and your current technique?

5. What training/education did your receive on sterile technique, prior to and during your employment?

6. Do you have to demonstrate your current sterile technique in a structured controlled setting such as a simulation center?

The answers were the following:

1. Yes. 99 percent answered and recognized the importance of hand hygiene

2. No. 95 percent did not know their compliance

3. No. 97 percent did not know the methodology followed.

4. No. 95 percent said that they got training in nursing school on operating room technique but that floor nursing didn’t apply OR standards

5. No. 95 percent said no additional training in sterile technique, although occasional training on hand hygiene

6. No. 98 percent said that their competency never used a simulation center to validate.

So, are we teaching the wrong thing? Should we be teaching a higher level of performance? Are we not using our resources to best optimize performance? Are we holding ourselves accountable and training to a higher standard?

Did you ever wonder why hand hygiene compliance and sterile technique is typically higher in nurses that come from an OR background? Let me define “OR sterile technique” for the purpose of this column. OR sterile technique is the logical understanding, awareness and practice of movements by personnel to prevent the introduction and movement of pathogens within the OR space. For the purpose of this article, I shall exclude handwashing/scrub protocols for they are different for OR and floor nursing. However, once “scrubbed in,” the principles are the same. What are you doing with your hands and what are you touching -- whether un-gloved or gloved -- are vehicles for the pathogens to become mobile.

We need to raise the bar from minimum standards to evidence based standards in our education/training programs. As they also say in surgical training, “See one, do one, teach one.” Here are some suggestions:

1. Create a culture of evidence-based training/education, with minimum standards being unacceptable

2. Elevate all your techniques/protocols to the OR standard of sterile technique

3. Use technology to provide real-time data on performance improvement

4. Use scorecards, dashboards and feedback tools to reward performance and identify need for additional training/education

5. Consider using a simulation center to train, educate and monitor actual knowledge in a structured environment

6. Utilize an annual certification process in which individuals should be required to pass a written and practicum annually for hand hygiene and sterile technique proficiency

7. Reward and recognize by incentivizing individuals. An idea would be our “gold star” patient safety performance ID badge. Note: three gold stars indicate trained, certified and current performance criteria achieved.

How do you use your simulation center to assist you?

• To establish your training and education best practices as a collaboration

• Every staff member must pass through and demonstrate proficiency within the practicum

• Certification and re-certification for all nursing, physicians, and other healthcare personnel

• Remedial education/training/re-training

• New hires, temps, and administrative personnel must be certified

• If compliance technology used, the technology should be installed in the simulation center.

In summary, we need to do more. We need to raise the bar. We need to be aggressive and creative in our approach to fighting pathogens. Pathogens have no rules.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene and Surfaces: How a Performance Improvement Team and Lean 6 Sigma Methodology Helped to Improve Hand Hygiene Compliance and Eliminate Practice Errors

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

There’s a saying that pathogens don’t have legs, we give them legs. When we can limit their mobility, we lower the risk of infection. When the pathogen cannot reach the host, it eventually dies. So, why are we still experiencing more than 2 million infections per year and more than 100,000 deaths in the acute care setting and 400,000 deaths in the alternate-site setting, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)?

Hand hygiene is considered the No. 1 preventive methods for reducing the risk of infection. Hand hygiene is a process of sanitizing your hands and doing this at the proper time. Within this article I would like to address and focus on the latter at the proper time.

For this exercise, we called upon our performance improvement team and their Lean 6 Sigma playbook. Lean is the performance improvement process of eliminating “waste” and redefining a correct process. When married with 6-Sigma, chances for error and mistakes are identified. The engagement begins by selecting the correct cross functional team to participate. We then begin “the current state” analysis, which is collecting data on current activities and mapping this to a workflow pictorial called a “spaghetti diagram."

Step 1

Assess the current state

Step 2

• Identify improvements in workflow eliminating wasted steps and opportunities for errors

• Standardize workflow process for all rooms

• Relocate and move assets to the same place in each room

• Align this standardized process with hand hygiene process, so that hand hygiene is performed the same for each room

• Allocate and relocate dispensers to the most efficient location

• Should a dispenser be placed at the bedside? Next to a workstation?

Step 3

• Establish metrics

• Measure results

• Repeat the process

Most hospital workflows vary so much, even from unit to unit, that it is challenging to train staff; many are temps and travelers. The purpose of the lean process is to create a standard workflow and work footprint where with minimal training and orientation, the staff does not have to adjust to variations in these workflows, creating a chance for error and non-compliance. An example of where we used this concept is the emergency department (ED). By mirroring each room as an identical reflection of best practice, ED personnel don’t have to think where items are. They are there every time. In an emergency, you don’t have time to think; your training, memory and habits take over.

By identifying the correct process and labeling when to execute proper hand hygiene for that unit, a high level of proficiency and compliance can be achieved. The pain of change in behavior no longer exists because routine and habit become natural. We must make it easy to be compliant by giving our teams the proper workflow, aligned with proper hand hygiene to be successful.

In conclusion, give your performance improvement team a call and try to engage with them in a project. It will not only be productive it will be fun.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX- The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

The Intersection of Infection, Immunity, Therapeutics, Nutrition, Prevention and Data

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary says that infection is “the state produced by the establishment of one or more pathogenic agents (such as a bacteria, protozoans, or viruses) in or on the body of a suitable host.1 The reaction between the pathogen and a host is critical to the ultimate outcome of any infection. Indeed, it is the host response that results in the symptoms of infection. As a pathogen multiplies, the host’s immune system responds to the microorganism and its toxins with the clinical symptoms of infection, e.g., fever, chills, malaise, etc.

The healthcare community is focused on treatment, but prevention is equally, and in some instances -- such as the COVID pandemic -- more important. There is an amazing array of antimicrobial agents available to treat infections in U.S. healthcare settings. However, preventive endeavors are both more difficult and time intensive than simply administering a medication. Microorganisms can evolve quickly to antimicrobials, often becoming resistant to these agents through acquisition of genetic factors that inactivate or prevent an antimicrobial’s ability to assist the immune system and eradicate a pathogen.

An effective defensive structure against infection might be garnered from our military and their defense of high-value targets. Through the deployment of a series of rings and barriers they attempt to thwart any enemy rather than engage in battle. Is infection prevention the use of the same principles to protect patients?

The Rings of a Good Defense

Data, accurate and real time, is essential, as early intelligence is the backbone of any defense. Examples might include better public health resources, central databases and dashboards, etc. Critical information can be manipulated and limited but accurate, raw date is often critical to provide health care professionals usable and actionable information to initiate the appropriate interventions to both prevent infection and treat patients.

Nutrition can also impact the effectiveness of our immune systems to both prevent and, if prevention fails, treat patients’ infections. One of the critical components of infection prevention and response to infection is an intact immune system. Patients with immunodeficiency are much more vulnerable to infections, and hence, any intervention that improves immunocompetency can improve resistance to and hence prevention of infection.

Prevention is the third ring of defense. If a pathogen is prevented from reaching the patient, then we avoid both the necessity of treatment as well the risk of morbidity and mortality.. Two critical methods of prevention are hand hygiene and surface cleaning. Hands can provide a mode of transmission of pathogens from a surface or another patient with an infection to another, initially uninfected patient. Surfaces in the patent’s environment are often contaminated with microorganisms and may serve as a reservoir of pathogens. Proper disinfection of a surface/area reduces bioburden and consequently prevents a healthcare worker’s acquisition of that organism via hand contact with subsequent potential transmission to a new host. Proper hand hygiene is a second critical component of prevention, as it can eradicate or, minimally, reduce the numbers of microorganisms present. Of importance, these two interventions act synergistically to prevent infection.

Vaccines can also effectively prevent infection, but are only available for certain infections, such as common childhood infections such as measles and mumps, as well as other infections that may affect all age groups, such as influenza and COVID. A vaccine is antigenic material that precipitates an immune response specific to that pathogen, but does not harm the host or precipitate the actual infection, resulting in memory cells and antibodies that are available to the host’s immune system should the host encounter that specific pathogen in the future. Indeed, vaccines have had the greatest impact on disease prevention and the increasing longevity of populations.

Therapeutics, as noted above, are the antimicrobial agents used to treat established infections and in certain instances, such asd surgical prophylaxis and patients with compromised immune systems, prevent infection. These agents are critical in the treatment of infection when our preventive efforts fail.

Immunity is the immunologic and cellular responses to foreign antigens, in this example an infectious agent. This coordinated response is critical to protect the host from the foreign antigens that an individual is exposed to during their lifetime. In some cases, previous vaccination or previous infection with a pathogen results in the production of antibodies specific to that previous exposure. When re-exposed to that pathogen, memory cells are recruited that code for the production of the antibodies specific to the previously encountered pathogen. This results in the coordinated recruitment of the immune system to address and eradicate the infecting microorganism before they multiply and cause a clinically evident infection. When infected by a pathogen to which the host has no previous experience, a much more complicated immune response occurs, leading over a longer period of time to the production of antibodies as noted above.

Many individuals are more prone to infection, e.g., the very young, the very old, those with chronic disease, the immunocompromised, surgical patients with the interruption of their cutaneous protective barrier, and even presence in a hospital where antibiotics and severity of illness create an environment with resistant pathogens. Preventive efforts (the front end) become a critically important method to avoid infection, a much more effective intervention than treating an infection (the back end), often with resistant pathogens.

In summary, hopefully this discussion outlines the factors to be considered when discussing infections. Further, it also provides some insight into treatment versus infection and both the challenges and the value surrounding preventive interventions.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX- The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

Hand Hygiene and Environmental Hygiene: Making the Case for Automating and Implementing Simultaneously to Move the Needle on HAIs

By Robert P. Lee

This article originally appeared in the January 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Septimus, et al. (2014) note that “Over the last decade, the general approaches to healthcare-associated infection (HAI) prevention have taken two conceptually different paths: Vertical approaches that aim to reduce colonization, infection, and transmission of specific pathogens, largely through use of active surveillance testing (AST) to identify carriers, followed by implementation of measures aimed at preventing transmission from carriers to other patients, and horizontal approaches that aim to reduce the risk of infections due to a broad array of pathogens through implementation of standardized practices that do not depend on patient-specific conditions. Examples of horizontal infection prevention strategies include minimizing the un-necessary use of invasive medical devices, enhancing hand hygiene, improving environmental cleaning, and promoting antimicrobial stewardship. Although vertical and horizontal approaches are not mutually exclusive and are often intermixed, some experts believe that the horizontal approach under usual endemic situations may offer the best overall value given the diversity of microorganisms that can cause HAIs and the constrained resources available for infection prevention efforts. When informed by local knowledge of microbial epidemiology and ecology and supported by a strong quality improvement program, this strategy allows healthcare facilities to focus on approaches that target all rather than selected organisms in the absence of an organism-specific epidemic.”

The authors of this paper clearly understand that a single intervention will not move the needle on HAIs to the point where HAI reduction is measurable, and cause-and-effect can be assigned. As we know from Deming, “If you can’t measure, you can’t manage,” or put another way, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” So, what if we take two interventions and combine their attributes and link their data; these two are hand hygiene and environmental hygiene.

Let’s start with definitions. What is hand hygiene? Hand hygiene should not be confused with handwashing. Hand hygiene is the methodology, understanding and the execution of sanitizing your hands at the right time with the appropriate sanitizing agents, which might include soap/water or an approved waterless agent. The key to hand hygiene is knowing when and then executing on the proper process of how. When to do hand hygiene is very simple, you must assume that anything you touch with your hands provides a source of contamination. The hands are the transfer vehicle. Examples could include equipment, keyboards, cell phones, all surfaces. Items you should think about are items that are medical devices such as face masks and disposable gloves. All of these can harbor pathogens and with the help of your hands can transfer these pathogens to you, the patient, or other host.

What is environmental hygiene? “Environmental hygiene is maintaining a clean environment by cleaning equipment between use, disinfecting surfaces, and sterilizing medical equipment according to best practices to remove and destroy potential infectious microorganisms.” Essentially, we want to reduce the bioburden or viral load in our surroundings. The processes and tools will be discussed in future writings in this column.

So, let me tie these two interventions together and explain why they are synergistic. In simple terms, if we start with zero bioburden and maintain zero bioburden on surfaces, we reduce the risk that a microorganism will be available to transfer. Is this possible? Maybe not. We know that the hands are the major source of mobility for microorganisms, and with hand hygiene compliance within the healthcare sector averaging less than 38 percent according to the CDC and less than 25 percent when measured electronically, we should be concerned about environmental hygiene and hand hygiene together.

In a recent study completed in a Florida hospital, it was suggested to measure hand hygiene and environmental hygiene compliance simultaneously. Proprietary technology was used to gather data on nursing, physician, and hospital staff (environmental services professionals). This hospital was selected because they had just received the state of Florida award for being “best in practice” for their environmental hygiene. One of the benefits of technology is that they were able to acquire significant data in a short period of time (more than 40,000 opportunities in 10 days). The results, presented to hospital administration, were eye-opening:

• Hand hygiene compliance: Nursing,c33 percent; physicians, 29 percent; staff (EVS), 24 percent

• Environmental hygiene compliance (L&D Unit)

- 23 rooms, 17 occupied

- Rooms require three visits from EVS daily: introduction, cleaning, and revisit QA check

- Data showed of the 17 rooms occupied, that only three visits in three days made by EVS personnel, not daily

- During a 10-minute period that EVS personnel visited eight patient bathrooms, never changing gloves or performing hand hygiene

Nothing was ever heard from administration after this meeting. Key takeaways from this effort were that more accountability is needed in the hand hygiene and environmental hygiene space. Technology can help to validate and reduce time in gathering data. Data puts you in control.

As a final thought, with the help of technology, if we could create more accountability between hand hygiene and environmental hygiene, what might the optimal levels be to move the needle on HAI? Clearly, 100 percent is not achievable, but maybe 60 percent to 70 percent is.

Robert Lee, BA, the CEO and founder of MD-Medical Data Quality & Safety Advisors, LLC, is the senior biologist and performance improvement consultant. MD-MDQSA is the home of The IPEX - The Infection Prevention Exchange, a digital collaboration between selected evidence-based solutions that use big data, technology, and AI to reduce risk of HAIs.

References:

Septimus E, MD, Weinstein RA, Perl TM, Goldmann DA and Yokoe DS. Commentary: Approaches for Preventing Healthcare-Associated Infections: Go Long or Go Wide? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Vol. 35, No. 7, July 2014.

Marschall J, Mermel LA, Fakih M, et al. Strategies to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35(7): 753-771.

Calfee DP, Salgado CD, Milstone AM, et al. Strategies to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission and in-fection in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(7):772-796.