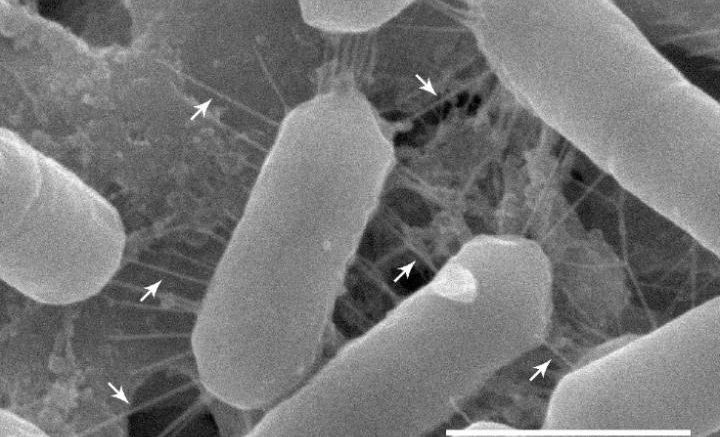

This scanning electron microscopy image of the Lacticaseibacillus casei AMBR2 strain from the nose shows long, spike-like fimbriae that allow the bacteria to adhere to the cell surface of our nose. Courtesy of De Boeck et al. / Cell Reports

Beneficial strains of bacteria residing in our guts, genital tracts, and skin have been shown to play a role in human health, and now, researchers publishing May 26 in the journal Cell Reports suggest that some of these "good" bacteria also have a niche in our noses. They found that people with chronic nasal and sinus inflammation had fewer lactobacilli in their upper respiratory tract than healthy controls and were able to identify a specific strain of the bacteria that has evolved to better survive the oxygen-rich environment of the nose. As a part of their study, the researchers developed a proof-of-concept nasal spray that could deliver lactobacilli to the nose, where the bacteria were able to colonize the upper respiratory tract of healthy volunteers.

Senior author Sarah Lebeer of the University of Antwerp became interested in the microbiota of the nose when her mother underwent a surgery for lifelong problems with headaches and chronic rhinosinusitis. "My mother had tried many different treatments, but none worked. I was thinking it's a pity that I could not advise her some good bacteria or probiotics for the nose," recalled Lebeer, who was previously studying gut and vaginal probiotics. "No one had ever really studied it."

To see whether the bacteria we associate with gut health also play a role in the health of the upper respiratory tract, Lebeer and her Procure team (http://www.procureproject.be/) compared nose bacteria between 100 healthy individuals and 225 chronic rhinosinusitis patients. They looked at the prevalence of 30 different families of bacteria in the upper respiratory tract of their participants and found that the healthy people had a greater abundance of lactobacilli than the patients--up to 10 times more in some parts of the nose. Lactobacilli are well-known beneficial, rod-shaped bacteria that have pathogen-inhibiting properties because they produce lactic acid through sugar fermentation, but these bacteria had never been studied in detail in the nose.

The researchers took a closer look and discovered a specific strain of the Lacticaseibacillus that not only showed some anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects against pathogens but also unique features that enables the strain to better adapt to the environment of the nose. Although most lactobacilli prefer to grow in the absence of oxygen, the identified strain showed unique genes making it able to cope with the higher oxidative stress levels in the nose. Moreover, the researchers observed the bacteria covered with flexible, hair-like tubes called fimbriae, which allow them to adhere to the surface cells in the nose, indicating an interaction between the bacteria and host.

The researchers then sought to verify their findings in vivo. However, "one limitation is that there are actually no real good animal models or mechanistic models to study the interaction of nose bacteria and human host," says Lebeer. "The microbiome of the nose of mice compared with humans, it's certainly different. Also, mice are nose breathers and they don't get chronic rhinosinusitis; they have fewer allergies and inflammations."

But the results from the lab, and the long history of safe use of lactobacilli, allowed the researchers to study the bacteria in humans instead of animal models. The team created a kind of "probiotic nasal spray" with a selected lactobacillus strain in a special formulation for 20 healthy volunteers. Introducing bacteria to the nose can be challenging, because it's so good at filtering out foreign substances; any substance introduced to the nose usually disappears within 15 minutes. However, after two weeks of administering the spray twice daily, the bacteria stayed in the nose longer than 15 minutes--they colonized the nose for up to two weeks without adverse effects. The study of the spray was not set up to look at beneficial effects, although anecdotally some participants mentioned having fewer nasal problems and said they could breathe better.

The next step for the researchers is to understand whether the fimbriae and the ability to endure oxidative stress are key to beneficial anti-inflammatory properties of the strain, as well as to identify which antimicrobial molecules the strain produces in addition to lactic acid. Ultimately, the team's goal is to develop therapeutics based on nasal probiotics to improve the symptoms of sinusitis patients.

"Sinusitis patients don't have a lot of treatment options," says Lebeer, and with the treatments that are available, problems such as antibiotic resistance and side effects often arise. "We think that certain patients would benefit from remodeling their microbiome and introducing beneficial bacteria in their nose to reduce certain symptoms. But we still have a long way to go with clinical and further mechanistic studies."

This research was supported by the Flanders Innovation and Entrepreneurship Agency, the University of Antwerp, and by the personal grants of Ilke De Boeck, Stijn Wittouck, Camille Allonsius, and Sander Wuyts.

Reference: Cell Reports, De Boeck et al. Lactobacilli have a niche in the human nose. https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(20)30627-6

Source: Cell Press

Be the first to comment on "Humans Have Beneficial Bacteria Uniquely Adapted for Life in Our Noses"