Are Masks Really Not Working or Do We Need to Focus on Community-level Masking Education Around Proper Handling and Indications for Use?

By Shanina Knighton, PhD, RN, CIC

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

As we reflect on being what some people would describe as being out of the “eye of the storm” as it relates to COVID-19, there are many opinions and reflections about what worked well and what did not. One controversial scientific question that still exists is “are masks effective?” A few scientific reviews, including Cochrane1 suggest the effectiveness of masks were inconclusive, whereas mainstream media outlets shared the message that “masks do not work.”

As an infection preventionist, nurse and scientist, I understand that non-healthcare workers do not always understand how important proper wear and handling of masks are and the risks associated with mishandling and reuse2 of disposable masks. In healthcare, it is established that if masks are mishandled or improperly used, they can increase the risk for infection transmission between patients. For example, in the pre-pandemic era it was standard for surgical masks to be one-time use when needed for precautions and or if you had a patient that required airborne precautions you would be told to use a N-95 mask for just that patient during your shift. These measures helped decrease the risks of transmission. During the pandemic, emergency reuse was emphasized due to limited supplies favoring the opinion that mask reuse provided more of an upside for protection than risks. However, data was scarce in determining that.

As attention turns more to public health and community-level infection prevention and control efforts it intreats the scientific community to pause and ask, “Are we educating and measuring the effectiveness of basic infection prevention and control practices and in this example— mask use and handling including the practical uses that can keep everyday people safe. Furthermore, do we educate the community on the benefits of proper mask use and handling and the potential consequences associated with misuse and mishandling?

Briefly, I summarize some examples of misuse and education tips often overlooked.

Dirty hands taking the mask on and off parallels to a dirty mask. Hand hygiene is the simple most important wat to prevent the spread of germs that lead to infections. During the pandemic people were told to put on masks. However, evaluating if people clean their hands at all, less known correctly before and after putting their masks on should be considered. Mouths and noses expel germs and are also entry for germs. The mask coming in direct contact with the mouth and nose means that people run the risk of unknowingly transmitting germs directly to and from their face by way of the mask.

Dirty cell phones hashtag our third hand links to a dirty mask. Cell phones are seen as the third hand and are shown to be 10 times dirtier 3than a toilet seat. Cell phones create a segway to germs being directly transmitted to the face. Imagine your face, cell phone and mask all coming in contact with each other as you place your phone against your mask while keeping it on or pulling it down to take a call instead of removing it from ear to ear. Cell phones can get contaminated just because we use them for almost everything. People that do bathroom scrolling are at risk given many studies showing the splash effect from sinks4 and toilets5 thus justifying the transmission of some harmful germs. Mobile hygiene and touchscreen hygiene is important to avoiding germs that can travel to or from your “third hand.”

Mishandling and mis-wearing of masks connect to microbes. Treading through the hallways in many walks of life from emergency departments where the highest foot traffic occurs to COVID testing or vaccine clinics many people including healthcare workers could be observed time and time again wearing masks as chin girdles or beneath their nose while some wore them correctly above the bridge of their nose with a snug fit. Incorrect masking wearing means that the protection against particulates is inaccurate compared to what the manufacturer’s protection standards might say. Many factors such as not removing masks from ear to ear, sitting masks on unclean surfaces, wearing disposable masks multiple times because it is not “visibly” dirty and exposure of the mask under certain conditions can alter the effectiveness of how well a mask will protect someone. Education round correct technique and understanding of how to handle and wear masks is needed for community use of masks.

We won’t be masked forever, but we should when it matters. It is not likely people will wear masks while sitting privately in their cars forever. It is also not likely that masking will go away. Geographical areas where transmission is high, working with high-risk populations or being considered a part of a high-risk population warrants consideration for wearing masks according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention6. However, based on my expertise there are situations where transmission is at its highest that influences my personal masking habits. While I do not wear masks in every setting, I do wear them on public transportation7 where cleaning practices have slowed, and high air exchange is no longer occurring. I wear masks in old buildings8 where I know the heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems are not up to par. If I am in an elevator9 with strangers, I wear my mask. Unfortunately, you cannot predict when someone will have to cough or sneeze in these types of closed environments therefore, I would rather take my chances on wearing a mask for that short duration of time than coming in contact with droplets that can make me sick. Many agree that wearing masks in healthcare settings should go away, but I disagree. We know that within healthcare settings people are likely to go to facilities because they are sick including a higher likelihood to carry transmissible germs such as respiratory illnesses.

Disposable masks are disposable and do expire.10 It is understandable that resources at certain points during the pandemic were scarce. However, people should be aware that similarly to following directions on a box of food for preparation directions, masks have directions that include country of origin, expiration date and most importantly directions for use including the number of hours that you should wear them. Furthermore, similarly to how technology and food gets recalled, education around ensuring masks are breathable without restriction, how to inspect masks for defects, and proper reporting and discarding if you detect defects is important, yet something rarely considered during evaluation of mask effectiveness.

Notably, many healthcare protocols that are implemented in community settings are derived from healthcare settings as it relates to messaging about hand hygiene and proper mask wearing. While many heard “just wear the mask”— this led to many healthcare professionals observing people mishandle masks. Similar to many Infection Preventionists, we know that emphasis on mask education could have made a difference in COVID-19 outcomes and still can. People’s mistrust and belief that masks do not work can be negated with sharing the risks associated with improper handling, use and by providing education about mask safety.

Shanina Knighton, PhD, RN, CIC, is an associate professor at Case Western Reserve University.

References:

1. Jefferson T, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2023) doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub6.

2. Easwaran V, et al. Examining factors influencing public knowledge and practice of proper face mask usage during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. PeerJ 12, e16889 (2024).

3. Kõljalg S, et al. High level bacterial contamination of secondary school students’ mobile phones. Germs 7, 73–77 (2017).

4. Fucini G-B, et al. Sinks in patient rooms in ICUs are associated with higher rates of hospital-acquired infection: a retrospective analysis of 552 ICUs. J. Hosp. Infect. 139, 99–105 (2023).

5. Abney SE, et al. Toilet hygiene—review and research needs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 131, 2705–2714 (2021).

6. CDC. Use and Care of Masks. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/about-face-coverings.html.

7. FTA. Using Your Safety Management System (SMS) to Mitigate Infectious Disease and Respiratory Hazard Exposure. https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-programs/safety/using-your-safety-management-system-sms-mitigate-infectious-disease.

8. Burridge HC, et al. The ventilation of buildings and other mitigating measures for COVID-19: a focus on wintertime. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 477, 20200855.

9. Liu S and Deng Z. Transmission and infection risk of COVID-19 when people coughing in an elevator. Build. Environ. 238, 110343 (2023).

10. Health C for D and R. Face Masks, Barrier Face Coverings, Surgical Masks, and Respirators for COVID-19. FDA (2024).

Isolation: Pondering the Issues

By Carol Calabrese, RN, BS, T-CSCT, CHESP, CIC

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

During clinical rotation I vividly recall one of my fellow classmates passing medications and walking directly into a room in which the patient was on isolation precautions.

Practicing good isolation techniques is important. We saw this especially in 2014 with the risk of Ebola in the United States. Everyone was franticly trying to re-educate their staff on donning and doffing technique of personal protective equipment (PPE). After the emergency was over, staff went back to their old bad habits. I have asked myself, are they old habits or did they never receive proper education? Are we doing enough isolation education for all healthcare workers (HCWs)?

How, where and when is education provided to HCWs in your institution? Infection preventionists (IPs) struggle to provide much-needed content during hospital orientation which has gone from an hour to just 15-30 minutes. If it is not provided in general orientation, then where is it provided? It might be in the unit/department’s orientation; and if it is, who has trained the preceptors in these locations? Are competencies performed?

With the emphasis we place on isolation, we may not be evaluating many of the issues related to caring for patients/residents that need to be in isolation.

I’ve seen a wide range of infractions. Staff wearing the gown backwards, leaving a gap in the front; staff walking out of isolation with a specimen, taking it to the nurses station to send through the pneumatic tube system; water pitchers being filled incorrectly, dietary walking out of a contact isolation room with the menu and then faxing it to dietary at the nurses station, a respiratory therapist in full PPE at the doorway of the room typing on the computer at the mobile work station; the whole endoscopy cart in contact precautions and a CNA doing one-to-one care in contact precautions without PPE, to name a few.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides clear guidance for donning and doffing PPE, how to manage linen and to use certain disposable equipment but does not discuss other activities involved in patient care.

When a staff member is doing one-to-one care, the typical expectation is that they are wearing PPE for an eight- to12-hour shift, minus breaks. I wonder how realistic an expectation this is. A thought I have had but never implemented is to provide the HCW with hospital-provided scrubs and a lab coat. The HCW would wear the scrubs while doing one-to-one, don the lab coat when they leave the room for breaks and place it on a hook outside of the patient’s room upon re-entry. Naturally hand hygiene is very important prior to donning and doffing the lab coat.

Staff are encouraged to identify all supplies that need to be taken into the room to provide care, however, issues arise with items coming out.

When I trained, we were taught to have a “buddy” that would assist us. I went into the isolation room to collect a urine specimen. I collected the specimen and labelled it. My buddy is outside of the room with the specimen bag, holding it open for me to place the specimen into it. They then took the specimen to the nursing station to send it to the laboratory. The outside of the specimen bag is not contaminated using this process. This process can and should be applied to other items coming out of an isolation room.

Evaluating how other departments providing care to the patient in Isolation are managing items used to care for that patient is critical. A nurse or CNA can be their buddy.

Does this take some coordination? Absolutely; however, it also aids in reducing the risk of transmission.

Over the past few years, research has demonstrated that pathogens such as C. difficile and other multidrug-resistant organisms (MRDOs) are being found in non-isolation rooms.

Teska and Gauthier (2021) suggest that IPs may need to consider having environmental services (EVS) personnel disinfect the floors of patients on Contact Precautions. The references cited discuss the transmission of pathogens between rooms via the shoes and hands of the HCWs.

With this evidence, IPs may also want to consider adding shoe covers to the necessary PPE worn for contact precautions.

The CDC’s CDI TAP Assessment Tool (2022) is helpful to evaluate what is being done to minimize the risk of transmission of CDI, however, I believe this should be utilized for all MDROs.

Per the CDC’s report, Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019, antimicrobial resistance (AR) report, it states that resistance is growing. Utilizing contact precautions will continue to grow as AR grows in addition to the threat of new and emerging pathogens.

As the draft 2024 transmission-based precautions guidance is released by CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), it may be time for us to take a deeper look at isolation technique, implementing the use of additional PPE and components to environmental hygiene.

Carol Calabrese, RN, BS, T-CSCT, CHESP, CIC, is an infection prevention consultant with 30-plus years of experience. Her experience includes many settings, acute to industry with leadership background. Connect with Carol on LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/carol-calabrese-rn-bs-t-csct-chesp-cic-a09bb216 and visit her website at: www.infectionpreventionconsultant.com

Should We Start Thinking More About Patient Hand Hygiene Education in Healthcare?

By Shanina C. Knighton, PhD, RN, CIC

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

For decades now, healthcare-associated infections continue to be an unyielding ongoing patient safety concern affecting millions of people and causing hundreds of thousands of deaths globally each year. The approach to preventing healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) differ from most patient safety issues as it has many factors associated with infection prevention and control especially for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), antibiotic-resistant organisms and viruses known as “superbugs” that are difficult to prevent and control.

Most innovative strategies to address HAIs focus specifically on antibiotic use, policy, hospital staff practices (e.g., not routinely cleaning hands) and hospital environmental factors (e.g., lack of extensive cleaning between patients). However, an important contributing factor to HAIs has received far less attention and study — the role of patients’ hands as a source of pathogen transmission in healthcare settings. Uncontended, most would argue that hand hygiene is the single most important practice for anyone to prevent the spread of pathogens that lead to HAIs, however there is less agreement on normalizing patient hand hygiene in healthcare settings. Scientific discovery regarding patients’ hand cleanliness and pathogen transmission is relatively new and emerging unlike decades of mounting evidence to support the healthcare worker transmission and hand hygiene.

Motivated from earlier science, healthcare staff hand hygiene has advanced immensely since the decades between the 1960s and the 1990s, confirming the carriage of pathogens on healthcare staff’s hands. Notably, in some of the same studies that recognized the carriage of pathogens on the hands of healthcare staff, results also showed that patients’ hands and bodies also tested positive for pathogens; furthermore, in some cases, patients were found to be the original carrier of these harmful organisms.1-5

Patients can transfer pathogens to their environment and to healthcare staff, and cross-contaminate themselves as germs are not unidirectional. Therefore, they can be transferred in various ways. Documented evidence shows that patients carry one or more MRDOs on their hands,6-9 proximal areas (trunk), and clothing10 thus increasing the risk of contaminating their environment or cross-contaminating themselves. Once admitted to hospitals, patients are at risk of getting or spreading HAIs simply by inadvertently and unknowingly transmitting pathogens from their hands by making contact with their own devices (some indwelling), dressings, surgical wounds, healing and non-healing ulcerations, IV sites, and orifices, including their mouths through making contact with their food.

Furthermore, patients frequently interact with nurses, doctors, visitors, and other patients, which can also increase risks for getting an HAI. While randomized controlled trials that address decolonization and isolation efforts repeatedly and effectively decreased pathogen transmission outside of the patients’ room and after patients are already infected,11 evidence supports bidirectional relationships between patients’ hand contamination and the contamination for high-touch environmental surfaces.12-15

Surfaces and tools commonly used by staff and patients such as bedside tables,12,16-17 bedrails,18 medical devices,12 or call lights contain MDROs.10,16 Contamination of patients’ personal belongings including cell phones19 and clothing10 also increases their risk of contact with MDROs (20,21). Hence, strategies to prevent growth and colonization of MDROs are needed. Recommendations and conclusions of earlier studies have contended that healthcare staff should clean their hands, but for patients, it was only suggested that patients could be a source of transmission resulting in minimal recommendations for patients to have clean hands.1,5 Accrediting bodies and governing entities acknowledge that patients should have an active role in their care to prevent HAIs; however, patients’ role in infection prevention is still passive. For example, patients are encouraged to ask healthcare staff to clean their hands before providing care, but rarely are educated on cleaning their own hands.

Patient hand hygiene as a quality improvement strategy can help prevent the transmission of pathogens that lead to HAIs while simultaneously promoting patient self-management and patient engagement. Furthermore, providing patients with the opportunity to clean their hands is an underutilized approach that can reduce patients’ hand contamination that can lead to infection. For uncontaminated patients, patient hand hygiene can provide an additional layer of protection for them to prevent predisposition to colonization that leads to HAIs. As viral bacterial and fungal infections increase and we continue to face multi-viral seasons comprised of influenza, SARS-CoV2, respiratory syncytial virus, pneumonia, and others it is timely to update the growing body of literature on the status of patient hand hygiene in hospitals, which can influence how we integrate or implement patient hand hygiene programs in acute care settings and long-term care settings.

Shanina C. Knighton, PhD, RN, CIC, is a nurse-scientist, infection preventionist and an associate professor in the Schools of Nursing and adjunct in biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University. Knighton was the Inaugural executive director of APIC’s Center for Research Practice and Innovation where she championed their transformation to advance science and practice. She is known for being able to take infection prevention science and turn it into practical and equitable tools for improvement in various settings. During COVID-19, she provided practical prevention tools and guidelines to community members, small businesses, community organizations and public officials including the state of Ohio, the American Nurses Association, the New York State Board of Education, and others. Her practical tips have appeared in media outlets including local news, Forbes, Fox News, Self magazine, and Modern Woman magazine. In 2022 she was recognized as a Case Western Reserve University Faculty Innovator.

References:

1. Casewell M, Phillips I. Hands as route of transmission for Klebsiella species. Br Med J. 1977 Nov 19;2(6098):1315–7.

2. Casewell MW, Desai N. Survival of multiply resistant Klebsiella aerogenes and other Gram-negative bacilli on fingertips. J Hosp Infect. 1983 Dec 1;4(4):350–60.

3. Gwaltney JM, Moskalski PB, Hendley JO. Hand-to-hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Apr;88(4):463–7.

4. Gwaltney JM. Rhinoviruses. Yale J Biol Med. 1975 Mar;48(1):17–45.

5. Sanderson PJ, Weissler S. Recovery of coliforms from the hands of nurses and patients: activities leading to contamination. J Hosp Infect. 1992 Jun;21(2):85–93.

6. Sunkesula VCK, Kundrapu S, Knighton S, Cadnum JL, Donskey CJ. A Randomized Trial to Determine the Impact of an Educational Patient Hand-Hygiene Intervention on Contamination of Hospitalized Patient’s Hands with Healthcare-Associated Pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017 Jan 5;1–3.

7. Cao J, Min L, Lansing B, Foxman B, Mody L. Multidrug-resistant organisms on patients’ hands: A missed opportunity. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 May 1;176(5):705–6.

8. Mody L, Krein SL, Saint SK, Min LC, Montoya A, Lansing B, et al. A Targeted Infection Prevention Intervention in Nursing Home Residents with Indwelling Devices. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 May 1;175(5):714–23.

9. Mody L, Washer LL, Kaye KS, Gibson K, Saint S, Reyes K, et al. Multidrug-resistant Organisms in Hospitals: What Is on Patient Hands and in Their Rooms? Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019 Apr 13.

10. Kanwar A, Cadnum JL, Thakur M, Jencson AL, Donskey CJ. Contaminated clothing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriers is a potential source of transmission. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. 2018 Jun 22 [cited 2018 Oct 14];0(0). Available from: https://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(18)30679-5/abstract

11. Peng HM, Wang LC, Zhai JL, Weng XS, Feng B, Wang W. Effectiveness of preoperative decolonization with nasal povidone iodine in Chinese patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery: a prospective cross-sectional study. Braz J Med Biol Res [Internet]. 2017 Dec 18 [cited 2018 Oct 14];51(2). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5734184/

12. Pilmis B, Billard-Pomares T, Martin M, Clarempuy C, Lemezo C, Saint-Marc C, et al. Can we explain environmental contamination by particular traits associated with patients? J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2019 Dec 20 [cited 2020 Jan 9]; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670119305328

13. Sethi AK, Al-Nassir WN, Nerandzic MM, Bobulsky GS, Donskey CJ. Persistence of skin contamination and environmental shedding of Clostridium difficile during and after treatment of C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010 Jan;31(1):21–7.

14. Weber DJ, Anderson D, Rutala WA. The role of the surface environment in healthcare-associated infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013 Aug;26(4):338–44.

15. Cheng VCC, Chau PH, Lee WM, Ho SKY, Lee DWY, So SYC, et al. Hand-touch contact assessment of high-touch and mutual-touch surfaces among healthcare workers, patients, and visitors. J Hosp Infect. 2015 Jul;90(3):220–5.

16. Boyce JM. Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J Hosp Infect. 2007 Jun;65 Suppl 2:50–4.

17. Dancer SJ. Controlling Hospital-Acquired Infection: Focus on the Role of the Environment and New Technologies for Decontamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014 Oct;27(4):665–90.

18. Hassan M, Gonzalez E, Hitchins V, Ilev I. Detecting bacteria contamination on medical device surfaces using an integrated fiber-optic mid-infrared spectroscopy sensing method. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2016 Aug 1; 231:646–54.

19. Tekerekoǧlu MS, Duman Y, Serindağ A, Cuǧlan SS, Kaysadu H, Tunc E, et al. Do mobile phones of patients, companions and visitors carry multidrug-resistant hospital pathogens? Am J Infect Control. 2011 Jun 1;39(5):379–81.

20. Sunkesula VCK, Kundrapu S, Knighton S, Cadnum JL, Donskey CJ. A Randomized Trial to Determine the Impact of an Educational Patient Hand-Hygiene Intervention on Contamination of Hospitalized Patient’s Hands with Healthcare-Associated Pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(5):595–7.

21. Rai H, Saldana C, Gonzalez-Orta MI, Knighton S, Cadnum JL, Donskey CJ. A pilot study to assess the impact of an educational patient hand hygiene intervention on acquisition of colonization with health care–associated pathogens. Am J Infect Control. 2019 Mar 1;47(3):334–6.

Infection Prevention and Advocacy: A Conversation About Appropriations and Policies to Enhance the Profession

This article originally appeared in the December 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Jill Holdsworth, MS, CIC, FAPIC, NREMT, CRCST, manager of infection prevention at Emory University Hospital Midtown, and Rich Capparell, director of legislative affairs for the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), discuss the importance of infection preventionists (IPs) advocating for their profession on Capitol Hill.

Jill Holdsworth: When we talk about advocacy for infection prevention, I don’t think many IPs know what that means or what the hot topics are. Can you give us a taste of what is most important right now?

Rich Capparell: Currently, Congress is struggling to come to an agreement on FY 2024 funding. The House of Representatives and Senate are very far apart, as House measures are looking to make heavy cuts to non-defense spending. APIC has been focused on preserving funding for key infection prevention and control programs, such as the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) and the Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Initiative (ARSI). Additionally, we are working with coalition partners to incentivize individuals to enter the infectious disease fields through the Bio-Preparedness Workforce Pilot Program. Although appropriations are important, APIC is also educating lawmakers about policies that will make patients safer. As we know, there are millions of healthcare-associated infections in nursing homes each year and government reports continue to highlight the need for stronger infection prevention and control programs. To see better outcomes, APIC is pushing Congress to require full-time infection preventionists in nursing homes and for these facilities to provide greater HAI data transparency. Finally, APIC is working with a wide array of partners to help support the antibiotic pipeline. To do this we are supporting the PASTEUR Act, which would establish a subscription-style program to provide federal contracts for a reliable supply of critically needed novel antimicrobials and not rely on the volume of sales like most other drugs on the market.

RC: You recently participated in the APIC Board of Directors Lobby Day. Can you share your experiences with Congressional staff (in-person vs virtual)?

JH: Last year, the APIC board of directors met virtually with the congressional staff, which was my first experience with APIC doing this type of work. It gave me the chance to educate myself more on topics most important to infection prevention on a higher level and being able to speak to it and really feel like I was making a difference for all of us and our patients by telling our congressional offices about these items. This fall, we were able to visit the offices in person, which gave us the chance to have a more in-depth conversation about the topics that was really engaging with the staff members. Each APIC board member had an APIC staff member with them and we presented the topics of interest, answered questions and had also done our homework on who we were meeting with, so we also knew what was important to them. This experience was incredible for me personally, allowing me to continue advocating for what is important in our profession, but also what our patients need most.

JH: I know most IPs are going to think they don’t have time for advocacy with everything else we have on our plates. What are some of the things, big and small in terms of time commitment, that IPs can do to make an impact?

RC: There are many ways for APIC members to get involved choose their level of engagement! The easiest way to stay engaged is via the APIC Action eList. This simple action can educate members on key activities and ways they can get involved in the future. For members interested in contacting legislators that aren’t sure what to say, I recommend the APIC Action Center. This resource has pre-written messages on key issues, that take less than a minute to send. Members looking to get more involved can volunteer to be their chapter’s legislative representatives or they can work with staff to start scheduling a virtual meeting with policymakers. Advocacy at any level helps get our message out, so we appreciate all levels of engagement!

RC: As follow-up to your question, what issue did you find most rewarding to talk about?

JH: I have to say I was surprised that it was easiest for me and most engaging to speak to the nursing home staffing ratios, even though that isn’t the setting I work in. This is something we should all be advocating for, as it does impact us all! I was able to speak to scenarios where I have tried to reach “the IP” at these facilities to communicate results, or receive results, and I couldn’t find anyone (or I got someone different each time I asked). The continuum of care is a very real struggle we will continue to deal with until we can ensure appropriate staffing in all facilities where infection prevention resources are needed.

Supplemental Disinfection Technology Use in Long Term-Care Facilities: How, When and Why

By Amanda Sivek, PhD, a-IPC

This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Editor’s note: This article is a summary of “UV Light and Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor Disinfection in LTC Settings: What You Need to Know” co-presented at the 2023 Kairos Education Conference & Exhibit with James Davis, manager of infection prevention and control services at ECRI.

Before the COVID pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC) estimated that 1 million to 3 million residents of long-term care facilities experienced a serious infection every year. Infection prevention and control (IP&C) practices can help vulnerable residents avoid getting infections from healthcare workers, other residents, and visitors. Environmental IP&C practices address cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces within residents’ rooms and day/common rooms.

At ECRI, we receive many questions from our members about supplemental disinfection technologies like ultraviolet (UV) light and hydrogen peroxide vapor (HPV) devices that are used in a variety of healthcare settings. Let’s discuss how UV light and HPV disinfection work, when these technologies could be used in long term care, and considerations for safely using UV and HPV devices in long term care facilities, such as assisted living facilities, nursing homes, and skilled nursing facilities.

How does UV light and HPV disinfection work?

UV-C light (200-280 nm) and UV-B light (280-315 nm) damage DNA/RNA to prohibit replication of microorganisms, ultimately killing them. UV-C light does not occur naturally on the Earth and is a known carcinogen. UV light disinfection effectiveness depends on the target surface’s distance from the UV light source, shadowing of the surface, and soil load on the target surface. UV light devices used in long term care facilities include UV room disinfection devices, air disinfection devices, UV mobile device disinfection boxes, handheld UV wands and UV phone boxes.

HPV decontamination devices use highly concentrated chemical sterilants to create a pure gas form of hydrogen peroxide that fills an enclosed, unoccupied space. HPV can decontaminate porous and nonporous surfaces within the treated space. A type of HPV decontamination device used in long term care facilities is a portable device with five components: a controller that initiates and tracks HPV device cycles; a dehumidifier that maintains the relative humidity within range to sustain HPV; a vaporizer that creates and disperses HPV with a measured amount of hydrogen peroxide; an aerator unit that breaks down HPV into water vapor and oxygen after the hydrogen peroxide contact time; and at least one hydrogen peroxide sensor that measures HPV concentration within an enclosed area and around sealed outer doors.

When could UV and HPV devices be used in long-term care facilities?

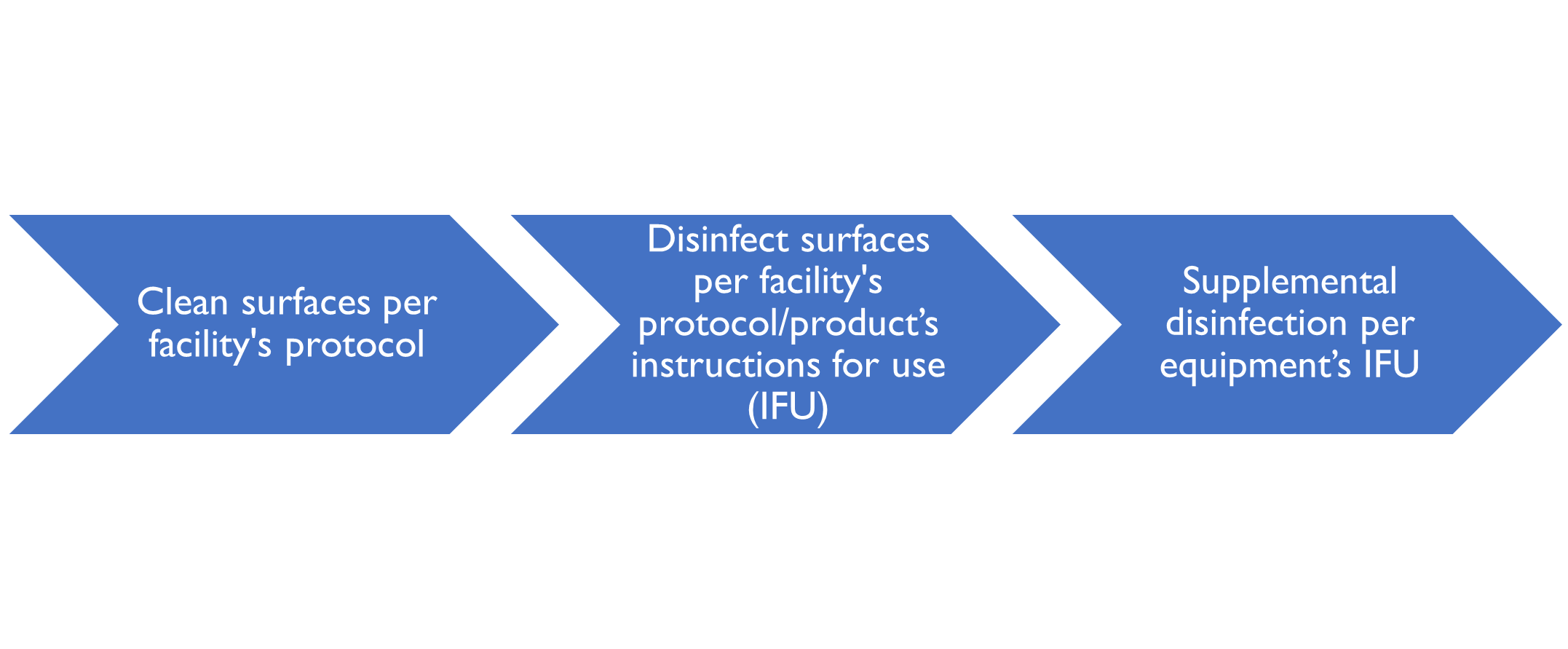

UV and HPV are supplemental disinfection modalities. They can be used after manual cleaning and disinfection methods are performed as shown in the following schematic:

Before using a supplemental disinfection method in a long-term care facility, the first step is to vacate the resident’s room, day room, or resident common area. It is imperative for staff and residents to avoid exposure to UV light and HPV. UV-C light is a carcinogen. Hydrogen peroxide vapor may cause asphyxiation in enclosed areas; other effects from inhalation may include gas embolism, unconsciousness, and respiratory arrest. Bottom line: Stay out of the room when supplemental disinfection devices are in use.

Typical UV Room Device Workflow

After vacating the room, the typical workflow for using a UV room disinfection device is to manually clean and disinfect surfaces within the space, following product IFUs. Next, the room is prepared by placing any safety sensors and the UV device within the room in the designated spots per facility protocol. Finally, the user selects the appropriate cycle, leaves the room, and initiates the disinfection cycle. After the 10- to 40-minute cycle completes, the user reenters the room and moves the device to the resident’s bathroom, another spot in the day/common room, or removes the device from the room.

Typical HPV Device Workflow

Before using a HPV decontamination device in a vacant, enclosed room, users must perform manual cleaning, disinfection, and drying of surfaces within the room, following product IFUs. Next, users should follow the HPV device IFU, which generally indicate to place the portable device in the room; seal HVAC vents, cover smoke detectors, and open cabinets/drawers in the room; place at least one chemical and biological indicator in the room; exit the room; seal all doors to the room using tape; and place a hazard sign at the sealed room doors.

Once the room is prepared, the user initiates a HPV cycle on the device controller and uses the handheld hydrogen peroxide sensor to verify that there is no HPV leakage around the outer doors. Several hours later after the HPV cycle completes, the user returns, unseals the room doors and cracks one door open. They hold the handheld hydrogen peroxide sensor within the room to verify that the chemical concentration is less than one part per million prior to room entry. Once verified, they unseal HVAC vents, uncover smoke detectors, and close cabinets/drawers within the room. Finally, the user documents the results of chemical and biological monitoring. If needed, the user responds to failed chemical and biological indicators per facility protocol.

Why use UV and HPV devices in long-term care facilities?

Supplemental disinfection technologies should only be used safely. Facilities should provide written protocols for each room that UV and HPV devices will be used, a list of any sensitive equipment that must be removed from the rooms, user training on the protocols, personal protective equipment that users should wear, and how users should respond to accidental UV and HPV exposure.

Amanda Sivek, PhD, a-IPC, is principal project engineer II, device evaluation, at ECRI.

ECRI Supplemental Disinfection Technology Resources:

- Evaluation Background: UV Room Disinfection Devices

- Evaluation Background: Countertop UV Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor Room Decontamination Devices

- Hydrogen Peroxide Room Disinfection for Preventing Healthcare-associated Infections

- Dry Hydrogen Peroxide Disinfection Systems for Reducing Healthcare-associated Infections

- Hasty Deployment of UV Disinfection Devices Can Reduce Effectiveness and Increase Exposure Risks(Hazard #6—Top 10 Health Technology Hazards for 2021)

- Avoiding Misuse of UVC Room Disinfection Technology

- Considerations for Clinical Use of Countertop UV Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: Chemical Fog Room Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: Electrostatically Augmented Disinfectant Spray Devices

- Technology Briefing: Far-UVC Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: Filtration and Germicidal UV Light for HVAC Applications

- Technology Briefing: Handheld UV Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: Permanent Environmental UV Disinfection Fixtures

- Technology Briefing: Portable Air Cleaners and UV Air Purifiers

- Technology Briefing: Upper-Air UV Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: UV Mobile Device Disinfection Boxes

- Technology Briefing: UV Phone Disinfection Boxes

- Technology Briefing: UV Room Disinfection Devices

- Technology Briefing: UV Shoe Sole Disinfection Devices

July 1: What is the Significance in Infection Prevention?

By Jill E. Holdsworth, MS, CIC, FAPIC, NREMT, CRCST

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Every year, July 1 comes around and, if you work in healthcare, you either love it or you dread it. Why? A new class of residents and fellows start in our facilities, and the trained, experienced physician trainees leave. There will always be those who feel July 1 means more medical errors and mistakes with less-experienced trainees; however, I have learned to take a different perspective—this is an incredibly exciting time where we can catch this new class when they first come in, teach them good habits right out of the gate so they will teach other residents that come after them correctly, thus creating a cascade effect of proper technique and practice. July 1 should be viewed as a significant opportunity in all areas of healthcare -- especially infection prevention!

It’s easier to dread July 1 than to see the silver lining, but why not try? Having new, bright minds ready to soak up every ounce of training and knowledge they can is such a powerful time. Residents want to do the right thing and they absolutely want to be taught correctly. When asked, many senior residents will tell you they were taught certain skills by the resident prior to them—thus the need to ensure all residents and fellows are taught basic infection prevention skills and knowledge correctly. How does this fit in with infection prevention? There are many ways infection preventionists (IPs) can impact how residents are learning, and thus help prevent infections.

One of my favorite memories of working with our teaching Head & Neck surgical team is when a resident came up to me before a case started in the operating room (OR) and held up a chemical indicator from a surgical drill tray that he had opened to prepare for the case and said, “I am not comfortable with how this indicator turned. I am going to send it back to the sterile processing department (SPD).” This was an incredible moment for our entire team and showed that we had come full circle in what we had talked about, learned and now were able to put it into action to keep our patients safe. But how did we get here?

You must put the time in as an IP — “Go to the Gemba,” as they say. This means to go where the work is done. When it comes to surgical teams, this may look different than your typical rounding with your nursing units, checking for isolation compliance and hand hygiene. To educate surgical teams, you first must understand their workflow, and to do this you must live it. I am the first to admit that this is not easy, and it means getting up very early and spending a lot of time with the team simply observing and learning. The first step is always spending time with the teams you are working with, getting to know their work, their barriers, and their work. When you gain their trust, they will learn from you as much as you learn from them.

When does the surgical team round? Who does the rounding? Who does the surgical prep in the OR? What is the resident’s role in the OR? Who marks the patients for clipping in pre-op? Do residents see the patients in pre-op? These questions will get you started with where you can make an impact with surgical site infection (SSI) protocols with your surgical team. In the past, we have surveyed a service line’s residents at the beginning of the year for general knowledge in skin-prep application techniques such as dry time, application time, as well as sterile processing practices such as checking blue wrap for holes, verifying sterility on chemical indicators, and asking questions about who taught them this information in the past. We spent the next year of their training teaching and emphasizing proper technique and protocols and then we surveyed them again at the end of the year and saw a significant difference in overall attitude and knowledge toward infection prevention processes.

When I spent time educating the surgical residents, I followed up on observing their cases alongside them, being in pre-op with them and tagging along during surgical rounds in the morning. Essentially, I became part of their team too. As an IP, we can either be a teammate or an auditor. I guarantee you that a teammate will get father every time. When I observe cases and attend surgical rounds, I don’t bring a clipboard or even a notebook. I put my hands up and let them know I am here to learn, listen and observe.

Teaching services also will have education sessions during their week—find when these sessions are and put yourself on the schedule. You can emphasize the educational topics you need to cover, show pictures of things you saw during rounds, ask questions about how you can help them, etc. When you become part of the solution, you become a teammate, and everyone begins working together. Everyone in the operating room should know how to check for sterility of instruments, perform an appropriate skin prep, and check an instrument wrap for a hole. When we partner with our physician trainees who may be doing these tasks, we can ensure not only that they are doing these tasks correctly and understand the importance, but that they pass down the correct information to the next class of trainees.

Jill E. Holdsworth, MS, CIC, FAPIC, NREMT, CRCST, is manager of the Infection Prevention Department at Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta.

Rationing Rather Than Omitting Care: A Nursing Expert Addresses an Alarming Trend

By Kelly M. Pyrek

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

In the February 2023 and April 2023 issues of Healthcare Hygiene magazine, we examined the impact of missed nursing care on patient safety as well as infection prevention and control. In this column, we feature a conversation with nursing expert Kasia Bail, PhD, a professor of gerontological nursing at the University of Canberra in Australia, about the tough choices nurses make during every shift.

Kasia Bail, PhD

HHM: What do you believe has been the impetus for the recent number of papers on missing care?

Kasia Bail: Given the time that it takes to establish research and publish it, I suspect that the surge in numbers has more to do with the prevalence of the issue and the momentum that science gains when there’s a phenomenon that justifies examination. Developing and examining evidence is slow and happens incrementally and has been building for the last 20 years.

HHM: Did COVID perhaps bring this issue to the forefront? And how might COVID have exacerbated an already problematic trend of missed nursing care?

KB: This has certainly been the case and there are publications to support it (See: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/30/8/639.abstract). I would argue that “missed nursing care” isn’t a new problem so much as it is a labeling of an ongoing issue. Nursing will always, and has always, rationed care in different ways. I think we need to involve the public in choosing what it wants nursing to ration. For example, my older nursing peers will often make jokes about how they used their time during shifts to make sure none of the pillowcase openings were facing the door, and to line up the wheels on the bed. Anecdotally, this was clinically and theoretically practical, to make sure the sand didn’t get into the pillowcases and the beds could be wheeled into the operating theatre promptly – various hang-ups from the Crimean War, perhaps. There is no evidence that I’m aware of, but one can assume nurses were choosing to use their time on these activities, rather than perhaps talking with patients or supporting family relationships or performing hygiene practices, which might have a stronger evidence base and cultural support now. Pillowcases and trolley wheels might sound like facetious examples, but the point being that the activities that nurses spend time on have always required prioritization; care has always been rationed. These days, if a nurse must choose between brushing someone’s teeth, administering a life-saving antibiotic on time, and admitting a new patient onto the ward so that a new bed can be created in the emergency department, it is logical that the teeth brushing will be the lowest priority. That doesn’t mean a nurse chooses not to do it but chooses not to do it right now and may choose to delay it within her shift or to hand it over to the next nurse. In the “Failure to Maintain” article I referred to, this kind of nurse decision making as “in-hospital triage.” I am a strong advocate for a “nurse interrupted” button in new digital information systems. Nurses work in multi-tasking, interrupted manners, yet many of the workflows being developed don’t recognize this and try to tie the nurse to the computer to complete her documentation. Nurses need to be able to make these decisions about immediate prioritization and be supported in delaying or postponing care but still communicating their need, to create a functional work environment that recognizes the reality of care rationing. Similarly, we need better data to help us make these decisions, and to support resourcing. For example, we often don’t have any clear measurable and comparable indicators about patient load – whether patients are self-caring and independent with showers or need bed sponges and two-hour wound dressings. Nurses are the flex of any hospital system, and we rely on their decision making within patient allocations and ward allocations to ensure care continues to be delivered. But that is rarely acknowledged in hospital governance systems, and minimal research. I recommend a key measure is the introduction of International Functional Standard – currently in use in rehabilitation hospitals only – to be included in acute-care hospitals for ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health). This would still be a crude measure, but it would provide some indication of workload. There are many in use across the world, but many are resource intensive and require nurses to do more work to identify how much work they must do, which is ironic.

HHM: Is the current focus on healthcare professional burnout and nurse exodus from the field peri- and post-pandemic perhaps shedding more light on the issue of missed nursing care?

KB: The professional burnout has been an ongoing issue, but not really addressed, hence the ongoing issues. The pandemic brought the underlying issues to the fore at a time when even the best health systems in the world are stretched. The National Health Service (NHS) reaching its 75th birthday has been highlighted about the conflation of expectations and health management strategies (See: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jun/17/fighting-for-life-by-isabel-hardman-our-nhs-by-andrew-seaton-review-the-nhs-at-75). The intersection between burnout and missed nursing care, and the factors that can ameliorate them, is a key area for research and intervention. The new attempt at Magnet rollout in Europe attests to this. (See: https://www.magnet4europe.eu/ and https://www.magnet4europe.eu/blog-page/four-questions-to-walter-sermeus)

HHM: Is the average nurse even aware of the concept of Cascade iatrogenesis? Is it a concept that should be included in nursing education?

KB: That’s a good question. Certainly, all the undergraduates in my university course would be exposed to this concept; however, university degrees are often contested with so many specialty areas vying for space. I suspect that as a complex issue it is perhaps not well covered (it would be a great research project for an honors or PhD student). Many health organizations don’t understand it well; all over the world we are trying to get the right balance of risk assessment (sometimes called comprehensive assessment), and then providing ameliorating or risk-modifying interventions. However, these are in addition to whatever the admitting diagnosis is (for hospitals, or other health services similarly). I would argue that cascade iatrogenesis is less the issue, than the ability of the staff to provide comprehensive care. In other research I’ve done it’s shown that nurses are under such pressure to complete the assessments – that is what is audited – but what care they provide to respond to that assessment is harder to audit. And so, there’s a perverse incentive, based on how clinical governance ends up working, that emphasizes the assessment and its documentation rather than the delivery of care. The reason this is an issue in relation to cascade iatrogenesis is that health services struggle to get the right balance to support staff to make decisions about patients that may be deteriorating. Missing someone’s cup of tea is a justifiable decision when it means making sure someone else’s antibiotic is administered on time. But when multiple cups of tea get missed, and then dehydration occurs, and then that isn’t assessed or identified and responded to, then the risk profile for that patient goes up. But arguably a large issue as to why cascade iatrogenesis may be occurring is less about what is taught, as what is translated into practice, and what is sustained based on the work environments. We also need to promote that the higher risk of complications means the need for higher prophylaxis. That sounds logical – when the risk for deep vein thrombosis is higher, there are protocols for clexane or heparin; when the risk for infection is higher, then there are protocols for antibiotic cover. However, with many of the competing nursing issues – confused patients, long wound dressings, complex medication regimes – there aren’t protocols to increase the prophylaxis, because the increased prophylaxis is increased nursing care. We have no clear way to “increase the nursing dose.” We rely on clever and articular shift managers, on ward managers communicating their needs to hospital administrators, or reviews of workload models, sometimes in conjunction with nursing unions. So, I would reiterate – we need to promote that higher risk of complications means the need for higher prophylaxis, and nursing care needs to be recognized and recommended as prophylaxis.

HHM: Do most nurses struggle with their decision to omit care, or is it more of an unconscious occurrence?

KB: This is a difficult question to answer. The old adage about “applying the oxygen mask to yourself before helping others” must be considered. Self-preservation is a natural response under threat – the increased pressure during covid that has intensified the front-line responses as well as public awareness of these tensions. Yes, nurses struggle with any decisions to omit care, but significantly, I would argue for the language of “rationing” rather than “omitting care.” All healthcare gets rationed, all health services make decisions about what they can and can’t provide, who’s within and who’s outside the boundaries of care, which medications make it to the subsidized list, which services are provided to which areas, which rural area gets the next diagnostic scanning machine (X-ray, MRI, CT, PET). But the difference with nurses is that it’s very direct, it is within the four walls of the ward that the decisions are made, which is all the more reason that the emotional labor of those nurses making the decisions must be considered. Research shows that many nurses leave roles when they are dissatisfied with the quality of care they are able to provide. But equally, yes, nurses will unconsciously omit care. There is research that highlights that some rationing of care can become habitual – that nurses may be used to being busy and get used to using the most streamlined approach they have developed to save them in times of duress. I believe patient teeth-brushing has been habitually sacrificed, and the evidence seems to back this, as one of the most commonly rationed nursing tasks. But my hospital used to have backup toothbrushes and toothpastes but no longer does; we hardly seem to have any kidney dishes and most of the patients are bedbound so without a kidney dish it’s hard to help them brush their teeth in bed. And not all wards stock the mouth buds, which quite frankly are fine for a quick mouth refresh for a dying patient but not particularly useful if someone needs a vigorous toothbrushing. So, if there isn’t the environmental nudge toward this good practice then it can reinforce this habitual de-prioritization. Will the after-hours shift coordinator prioritize delivery of a toothbrush at 9pm? I doubt it (I’m happy to be corrected!), but they would an antibiotic, so that helps you see what practices get enabled and prioritized systemwide. I think that increasingly missed nursing care is also being taught in the nursing curricula, particularly given the increasing science supporting and investigating the phenomena. I think the bigger issue is the shock that people experience about nurses having to ration their care. There will always be a finite number of resources. Health is no different to other areas of the economy, but arguably is dealing with the conflating issues of ageing populations, which means an increased volume of the population with complex illnesses that require ongoing treatment (rather than dying from their conditions); as well as increased expectations about health and medical care due to increased technology and specialization in responding to conditions, as well as increased transparency in terms of clinical governance. These do great things to support quality care, but they also put additional pressure on those settings to deliver. Nurses will always be the face of many of these health interactions, and in hospital settings in particular, the tensions between who receives the resource – in this case, nursing time -- is more visible.

HHM: In your study, were the nurses working as general floor/unit nurses or were they specifically tasked with infection control-related duties? Did this make any difference in their behavior?

KB: Seven of the 11 interviewees were directly in infection control nursing roles. The other four had varied roles which are specified. Further research, including quantitative research which seeks to differentiate different types of nurses and their value of infection control practices, would be interesting. I think this article highlights, however, that staffing needs to be controlled for the questions of “Do higher proportions of RNs affect the value placed on infection control? Or does a higher proportion of RNs reduce the incidence of missed nursing care?” Missed nursing care research is very hard to do prospectively however, hence the dearth of research in this arena.

HHM: Is missed care attributable to a gap in knowledge or a gap in practice, or both, and should this be a wake-up call that training and education need improvement?

KB: I think that is an oversimplification of complex issues, which is all too common in the interpretation of nursing work. I would encourage a review of the sections in our paper on the “whole of hospital” approach on pages 4-5. These nurses talked about how they needed to be able to talk convincingly to get the support of accountants to make appropriate purchases. The nurses also talked about there being excellent policies in place, but not enough nurses to make the policies deliverable. These are issues beyond teaching undergraduate nurses, or a gap in translating their learnings into practice – it’s a wake-up call that all layers of hospital administrators need to better understand and respect infection control nursing work, collect local data, and respond meaningfully.

HHM: Is it simply a matter of resourcing and staffing, to address missed nursing care in infection control-related practices, or is it also a behavioral issue/human factors engineering-related issue?

KB: It’s absolutely both. We know from the magnet hospital research, which has continued to be supported through decades of research (and increasing continental reach, with the European Magnet Hospital program in mid-delivery) that hospitals with good work environments have better outcomes. We know that the ingredients of these healthy work environments include resourcing and staffing as well as sound clinical governance and trusting and effective relationships between nurses, managers and other health professionals.

HHM: You make a very key statement in your paper when you observe “There are many situations of clinical care delivery that have not had robust research conducted to support the practice, despite widespread expert recommendations." This is a very big reason why many nurses in the U.S. believe they can skip some infection prevention-related practices, so how can this be addressed by health systems?

KB: Great question. Healthcare is always delivered in a state of uncertainty – evidence is continually being developed and refined, and some elements of care will always have a more theoretical principled approach and will not be able to develop a gold standard prospective clinical trial to “prove” an association or demonstrate the ‘best’ way. There’s an interesting article on the World Health Organization’s 5 Moments of Hand Hygiene highlighting the impracticality of this “protocol” which doesn’t have an evidence base. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t work – it is a very sound theoretical approach, and as an adoptable system has likely increased the hand hygiene practices and therefore infection rates. (See: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/31/4/322 and https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670123000725) Clinicians are accustomed to working in very messy settings where the group norms determine the practices, as well as making their own clinical decisions – that’s what they are paid to do, as registered health professionals. This is why some data and monitoring, as well as healthy working relationships, are crucial to be able to assess and interpret practices in an ongoing manner. Again, the magnet hospital approach supports this transparency and openness to practice development and change. (See: https://www.nursingworld.org/organizational-programs/magnet/magnet-model/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4431919/)

HHM: This is also a key observation from your paper: "Activities are prioritized in relation to the perceived impact of non-performance" -- are nurses taking it upon themselves to reject evidence-based practice because they think there is negligible impact on patients? Isn't this a potential undoing of any patient safety-first nursing care?

KB: I think that is an extreme interpretation, regarding “rejecting evidence-based practice.” The point of evidence-based practice is for the clinician to make interpretations of the evidence, and apply them in relation to the current situation, and their knowledge of the patient. I often tell my students to imagine they have one hand on the patient, one hand on their pile of textbooks and journals, and they themselves are the body in the middle with the eyes and ears to interpret the situation and try to make the best possible decision. I would argue that nurses work with a never-ending litany of contextually imagined yellow and red flags of possible future, potentially likely and actual and immediate threats to patient safety on a minute-by-minute basis. They manage this through “cognitive stacking” – continually re-prioritizing their mental list of tasks and worries as their shifts progress (See: https://journals.lww.com/jonajournal/Abstract/2005/07000/Understanding_the_Cognitive_Work_of_Nursing_in_the.4.aspx). It is exhausting, exacting and delicate work. They use their knowledge of their patients, biology, pathophysiology, pharmacology, hospital systems, hospital policies, hospital personalities and time and other resources to make these decisions on a minute-by-minute basis. An activity that will alleviate an immediate and actual threat to safety (and, of course, patient comfort) may need to take priority to a possible threat with a lower likelihood of risk outcome. It is a never-ending and constantly adapting risk matrix that the nurse conducts without much support. It has been argued that nurses would benefit from “clinical supervision” – the approach that psychologists use to reflect on the complexities of their role in working patients and use a mentor to help reflect on decision making and allow space for growth and adaptation. This is being taken up in a number of jurisdictions. This reflective practice would offer an opportunity to review practices and policies with a peer. Arguably this used to often happen in handovers, however handovers are now often done by tape recorder or at the bedside and/or with the computer, potentially limiting the reflecting learning space that they provided. In the style of magazine questionnaires, I have compiled some examples of the kinds of impossible decisions nurses deal with on a minute-by-minute basis:

- You have 10 minutes left in your shift. Do you:

- Check whether Mary’s pain relief has worked or if she needs another 5mg of endone.

- Check the emergency trolley and make sure all equipment is present and sterile if appropriate in case of a life-threatening code next shift.

- Go home early. You’ve already done two hours unpaid overtime this week.

- You are interrupted mid-task. Do you:

- Continue your task of educating Mr. Aliia regarding his colostomy bag, including infection control practices and emotional support for coming to terms with his new body

- Stop your current task, and attend to Mavis the patient in the next room who you have been told is nauseous and about to vomit

- Depends on whether you like Mr. Aliia or Mavis better

- You are set up to do a catheter insertion on Maria. You realize you may have touched the tip of the sterile catheter with your sterile glove but you’re not sure. Do you:

- Stop the procedure, and set it all up again, because the risk of infection is present and you would like to save Maria from that risk

- Continue the procedure, because you’re not certain you did touch it so the risk is small, and also because Maria is confused with delirium and also doesn’t speak English as a first language, so you think you would do more harm by lengthening the procedure, and also because relieving her distended bladder with the catheter may ease her delirium, which is a higher and more immediate risk than the risk of infection

- Call out to see if another nurse can help you make the decision

Reference: Bail K, et al. Missed infection control care and healthcare-associated infections: A qualitative study. Collegian. Vol. 28, Issue 4. Pages 393-399. August 2021.

Navigating the Environmental Protection Agency’s Lists of Disinfectants

By Katherine Lunt, MPH, MBA, CIC, HEM

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

In healthcare, cleaning and disinfection are extremely important to prevent the spread of infections. Cleaning is the physical removal of visible dirt, blood, body fluids, and other foreign material from objects and surfaces and must be performed prior to disinfection. Disinfection is the process of destroying microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi. There are three levels to categorize disinfectants: low-level, intermediate-level, and high-level disinfectants.

High-level disinfectants are intended to be used for critical and semi-critical medical devices and instruments; high-level disinfectants are regulated exclusively by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are not intended to be used on environmental surfaces. Intermediate-level disinfectants are intended to be used on some semi-critical items and non-critical items. Low-level disinfectants, such as environmental surface chemical disinfectants, are intended to be used on noncritical items. Intermediate-level and low-level disinfectants are regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and have EPA registration numbers.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Chemical Disinfectants

There are several types of disinfection methods used in healthcare. The most common method of environmental disinfection is chemical disinfection. Chemical disinfection is a process that uses chemicals to destroy microorganisms. Some common chemical disinfectants for environmental surface disinfection used in healthcare include alcohols, quaternary ammonium compounds, phenolics, and sodium hypochlorite (i.e., bleach). In the United States, the EPA regulates pesticides, including chemical disinfectants, used in healthcare to ensure they are safe and effective. An EPA-registered chemical disinfectant has been evaluated by the agency and certifies that the disinfectant is effective against the pathogens specified on the disinfectant’s label. Appendix A outlines the lists of antimicrobial products registered by the EPA.

The EPA requires laboratory potency testing for products to support product label claims. Chemical disinfectants labeled as “hospital disinfectant” have passed potency testing for activity against three representative organisms: Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella cholera suis. Hospital disinfectants that demonstrate potency against mycobacteria may include “tuberculocidal” on the label as well and are considered an intermediate-level disinfectant. A chemical disinfectant labeled as a hospital disinfectant without a tuberculocidal claim is considered a low-level disinfectant.

Selecting a Disinfectant on an EPA-Registered Disinfectant List

Chemical disinfectants are often marketed and sold under different brands and product names. To find out more information about a specific chemical disinfectant, locate the EPA-registration number on the product label. The EPA-registration number is listed on the product as EPA Reg. No. and is followed by two or three sets of numbers on the label. Search the EPA-registration number in the specific EPA-Registered Disinfectant List of the pathogen you are trying to kill exactly as the number appears on the label. If the disinfectant is EPA-certified, it will populate on the list and include the following information:

The Registration number is listed on the product. This is to help you identify the product on the EPA disinfectant lists.The Active Ingredient/s is the ingredient in the disinfectant that destroys the pathogen.

The Product Name is the common name of the product.

The Company is the manufacturer of the disinfectant.

The Contact Time in Minutes (“dwell time” or “wet time”) is the amount of time that the surface must remain wet for the disinfectant to work effectively.

The Formulation Type denotes whether the disinfectant is ready-to-use or requires a dilution for safe use.

The Surface Types describes the type of surfaces that this disinfectant can be used on. For example, many disinfectants can only be used on hard, nonporous surfaces, which would include most high-touch surfaces.

The Use Sites (Hospital, Institutional, Residential) are the settings where the product is intended to be used.

If there is not an EPA-registered disinfectant list available for a specific multidrug resistant organism (MDRO), search for a product claim against the organism or bacteria itself. To is important to highlight that MDRO denotes that the organism is resistant to treatment, not disinfection. MDROs are still susceptible to disinfection. Occasionally, a disinfectant will include kill claims against a specific MDRO. If the chemical disinfectant is effective against a drug-resistant form of the organism, it is effective against all forms of the organism.

Always follow the information on the product’s label and adhere to the instructions for use (IFU), personal protection equipment (PPE) requirements, and contact time to ensure maximum efficacy of the chemical disinfectant.

Appendix A – Antimicrobial Products Registered with EPA for Claims Against Common Pathogens

List A: Antimicrobial Products Registered with the EPA as Sterilizers

List B: Antimicrobial Products Registered with EPA for Claims Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB)

List C: EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Human HIV-1 Virus

List D: EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Human HIV-1 and Hepatitis B Virus

List E: EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Human HIV-1, and Hepatitis B Virus

List F: EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Hepatitis C Virus

List G: Antimicrobial Products Registered with EPA for Claims Against Norovirus (Feline calicivirus)

List H: EPA's Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and/or Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis or faecium (VRE)

List J: EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products for Medical Waste Treatment

List K: Antimicrobial Products Registered with EPA for Claims Against Clostridium difficile Spores

List L: Disinfectants for Use Against Ebola Virus

List M: Registered Antimicrobial Products with Label Claims for Avian Influenza

List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2

List O: Disinfectants for Use Against Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV2)

List P: Antimicrobial Products Registered with EPA for Claims Against Candida Auris

List Q: Disinfectants for Emerging Viral Pathogens (EVPs)

Katherine Lunt, MPH, MBA, CIC, HEM, is an infection preventionist with ECRI.

References:

CDC. 2019. Background E. Environmental Surfaces. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/background/services.html.

CDC. 2016. Chemical Disinfectants. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/disinfection-methods/chemical.html.

CDC. 2016. Cleaning. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/cleaning.html.

CDC. 2016. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities (2008), Tables and Figure: Table 1. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/tables/table1.html

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2022. Selected EPA-Registered Disinfectants. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/selected-epa-registered-disinfectants

WHO. 2018. Table 3.3.3, Spaulding Classification of Equipment Decontamination. In: Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536426/table/ch3.tab7/

Biofilms and Healthcare

By David W. Koenig, PhD

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of Healthcare Hygiene magazine.

Healthcare facilities -- such as hospitals, nursing homes and outpatient facilities -- are opportunistic locations for acquiring secondary infections unrelated to a patient's primary condition. Healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) are a primary concern for healthcare providers, administrators, and governments worldwide due to the reduced quality of healthcare and the considerable associated socioeconomic costs resulting from extended hospital stays for infection treatment.

Some of the most common HAI types occur during the use of indwelling medical devices, such as a catheter, endotracheal tube, feeding tube or prosthesis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the most common underlying cause of infections related to in-dwelling medical devices is the ability of microorganisms to adhere to the surface of devices and form biofilms. Biofilms are often associated with tissue infections such as chronic wounds, skin infections, endocarditis, chronic otitis media and cystic fibrosis.

Biofilms are a gathering of microbes that colonize various surfaces. Many biofilms are beneficial. The beneficial human microbiome consists of diverse biofilms on the skin, teeth and mucosa of the gut, nasal, and reproductive organs; however, if a biofilm contains pathogens, these biofilms can become a severe concern for healthcare facilities, leading to HAIs.

The aspect of most concern is increased resistance to antimicrobials and antibiotic therapy; because of this concern's broad acceptance that the most effective way to reduce the incidence of medical device-related infections is to prevent primary microbial adhesion and subsequent biofilm formation.

Biofilms produce an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that protects the microbes in the biofilm. EPS interferes with the penetration of antibiotics or antimicrobials through biofilm. EPS interference is compounded by the cells in the biofilm having an altered physiology that further protects those cells from any antimicrobial that might penetrate the biofilm. Biofilms also provide the microbes with an environment that allows cell-cell communication and quorum sensing and enhances the transfer of genetic elements and resistance genes. Indeed, biofilm bacteria can transform into a persistent state that mimics a spore. Ultimately, biofilms increase the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant microbes and the risk of transmission to the caretaker and patient.

Healthcare environmental biofilms can act as reservoirs for the transmission of pathogens. Biofilms are commonly associated with surfaces that remain wet; however, a biofilm cover surface does not necessarily have to appear watery to the eye for a biofilm to persist. Recently, dry surface biofilms have been receiving extensive study. Dry surface biofilms form an exterior veneer while the surface is wet and then dry when the moisture dissipates. Biofilm EPS plays a critical role in the persistence of a dry biofilm allowing the retention of enough water for sustained survival. Biofilm "hot spots" can include drains, sinks, plumbing connections, areas of toilets that remain wet and not cleaned with mechanical action, bathrooms, sink traps, air filtration mediums, window ledges and seals, air conditioning systems, fabrics, and carpets and rugs. Dry surface biofilms grow on various surfaces, such as blood pressure cuffs, intravenous poles, door handles, touch screens, and cell phones. Dispersion of cells from biofilms can perpetuate microbial resistance, recurrence, and transmission of dangerous pathogens in the healthcare environment.

The types of microbes associated with biofilms are very diverse. The most common bacteria associated with hospital device-related infections is Staphylococcus epidermidis. Other hospital biofilm bacteria are methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Viridans Streptococci, Enterococcus faecalis, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Recently, the fungi Candida auris has emerged as a critical biofilm-associated pathogen. Other medically associated fungi that form biofilms are Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, Coccidioides, and Pneumocystis— furthermore, human viruses and bacteriophages present in biofilms.

Control of biofilms is complex. For device-related biofilms, various prevention strategies are initiated. One process is to impregnate the device with leachable antimicrobials such as silver. Another is to coat the surface with anti-adherents that interfere with the initial attachment of the microbe to the surface, interfering with the 1st step of biofilm formation. There is also the possibility of imprinting micro-patterns on surfaces that inhibit biofilm formation. These tactics have allowed various levels of protection from biofilm formation on devices. Removing biofilms from animate surfaces commonly involves mechanical methods such as water jets and sonic disruption, widely found in dental cleaning.

Prevention and removal of biofilms on inanimate environmental surfaces are just as challenging. The biofilm is often on a surface that is hard to reach or in a dead leg within a water system. Cleaned and disinfected surfaces contiguous to the contaminated area can be readily re-contaminated by biofilm dispersion leading to a transmission hot spot. A strategy to help reduce surface recontamination is to employ a persistent antimicrobial. For example, copper-containing materials, such as bed rails, have prevented biofilm formation. Using a residual disinfectant may also be an excellent option to reduce the recontamination of a surface.