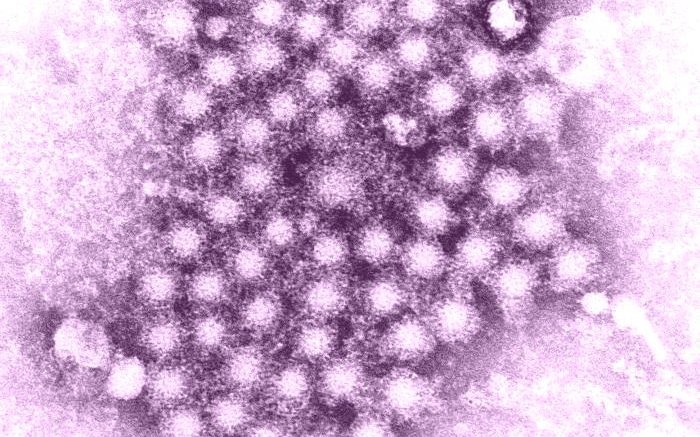

Millions of people in the U.S. and around the world are living with hepatitis C virus (HCV). But over the past decade, direct-acting antivirals (DAA) have proven effective against HCV, curing more than 95% of those who complete treatment. Traditionally, patients have had to wait at least 12 weeks after finishing treatment to find out if they are cured.

For the populations most affected by HCV, such as people who inject drugs (PWID), barriers to accessing care remain one of the biggest obstacles to eliminating hepatitis C in the United States. For many people, especially those facing unstable housing, transportation challenges, stigma, or financial insecurity, returning for multiple clinical visits is difficult or impossible. As a result, cures may go undocumented, and ongoing infections may remain undiagnosed and untreated.

To address these issues, a team of researchers from UC San Francisco examined whether providing HCV treatment at the time of diagnosis in a non-clinical community setting could improve antiviral treatment uptake for medically underserved populations.

In a study published December 19, 2025, in Open Forum Infectious Diseases, the researchers found that in a sample of PWID patients receiving an accelerated HCV test-and-treat protocol, results at the completion of treatment and 4 weeks post-treatment predicted those at 12 weeks post-treatment.

“This study shows that we can simplify hepatitis C care without compromising accuracy,” said study senior author Meghan Morris, PhD, MPH, UCSF professor of epidemiology and biostatistics. “Earlier testing doesn’t just confirm cure sooner. It also helps identify the small number of people who don’t clear the virus, so they can be quickly linked back to care instead of being lost in a system that is hard to access.”

The researchers’ findings were the result of a single-arm, non-randomized controlled trial – the No One Waits (NOW) study (NCT03987503) – assessing the effectiveness of HCV treatment initiation at the point of HCV infection diagnosis in a non-clinical community setting. Their population included 89 people most of whom injected drugs and were experiencing homelessness, recruited via convenience sampling, targeting people at high risk for HCV through street outreach and community-based referrals.

Participants who tested positive for a chronic HCV infection (reactive antibody and detected HCV RNA) were offered to immediately start a standard-of-care, 12-week course of the DAA Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir (SOF/VEL). Blood serum was collected to quantitatively test for HCV RNA at treatment completion, and at four and twelve weeks post-treatment. (An HCV cure is currently determined by an HCV RNA viral-load test at twelve or more weeks after treatment has been completed {SVR12}).

Among the 69 patients who completed treatment and had an HCV RNA result at SVR12 and at least one earlier time point, undetectable HCV RNA at treatment completion predicted cure at 12 weeks in 96.6% of cases, and undetectable HCV RNA at four weeks post-treatment predicted a cure in all cases. When the virus was still detectable at either earlier time point, all such individuals were correctly identified as not yet cured.

“Large clinical trials have previously shown that viral suppression four weeks after treatment strongly predicts long-term cure,” said Morris. “However, those studies largely included participants with stable access to healthcare and reliable follow-up. This study extends that evidence to real-world community settings and to populations most affected by hepatitis C, who are often underrepresented in clinical research.”

While national guidelines have defined cure at 12 weeks post-treatment, the findings support a growing body of evidence that earlier assessment can be a reliable and practical option in many care settings.

“This study demonstrates that point-of diagnosis direct-acting antiviral initiation was feasible, acceptable, and safe,” said Jennifer C. Price, MD, a hepatologist and UCSF Professor of Medicine. “These results support current efforts to apply SVR4 as an alternative endpoint for uncomplicated cases of HCV and highlight why treatment completion may also be seen as a reasonable endpoint in some contexts.”

Source: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)