When infectious diseases surge, response often comes down to timing: whether communities can position the right people and supplies before case counts spike.

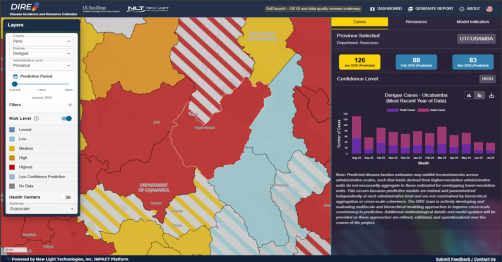

Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy are helping bridge that gap with a new platform designed to translate academic disease forecasting into actionable guidance for decision-makers. The Disease Incidence and Resource Estimator (DIRE) is an interactive map using geospatial predictive analytics that shows where dengue and malaria outbreaks are likely to occur— and what health resources may be needed to control and treat them.

“This project is about getting academic breakthroughs off the shelf and into the hands of the people making decisions,” said Gordon McCord, associate teaching professor at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy and the project’s principal investigator. “We took machine-learning models that predict dengue and turned them into something governments can actually use — so they can plan ahead and act before cases spike.”

McCord’s role in the project draws directly from his research track record: studying how weather and environmental conditions shape the spread of infectious disease and translating disease risk into financing estimates and other practical inputs that public health systems need.

DIRE focuses on Brazil and Peru, allowing users to view predicted disease risk at multiple geographic levels and see both recent trends and short-term projections. Users can click on a specific location to view past reported cases and projections for the current month and next two months, as well as a range of socio-economic and environmental indicators used in the model. The map also flags places where predictions are less certain, helping users weigh risk alongside uncertainty.

But the platform goes beyond forecasting. DIRE also estimates the quantity and cost of commodities and personnel required for disease control and treatment in each jurisdiction — turning predictions into planning inputs.

“It not only tells you how many cases of the disease are coming,” McCord said. “There’s a model underneath it that’s telling you how many resources would be needed in that place next month — how many doses of vaccine and what those costs would be, how many fumigation kits… It’s trying to do as much of the government’s job for it.”

DIRE can also generate downloadable PDF reports intended to be shared with local leaders — tools McCord described as useful for decision-makers who need a clear, place-specific picture of risk and readiness.

Dengue is becoming a bigger challenge in many parts of the world, including Latin America, as the factors that influence mosquito-borne disease continue to shift. McCord noted that in the Amazon and surrounding regions, climate change, land use change and deforestation — along with population movement into new areas — can increase human exposure.

Malaria remains a persistent threat in parts of Peru and Brazil and conditions in the Amazon can make control efforts especially complex. McCord pointed to links between ecological change and disease risk—where deforestation can alter mosquito habitats and bring more people into contact with transmission zones — and to the role that weather-related factors such as rain and flooding can play in expanding breeding sites.

DIRE is funded by a grant from the Wellcome Trust, a U.K.-based global health philanthropy, awarded to GPS to develop and deploy the platform together with New Light Technologies and in collaboration with UNICEF. Gabriel Carrasco-Escobar, who earned his doctorate in public health from UC San Diego, supported the work while in his role as assistant professor of epidemiology at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru.

The team also credits a broader user group that provided feedback during development, including colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Government of Peru, the Institute for Health Modeling and Climate Solutions in India and UNICEF regional offices, among others.

From the start, McCord said the project emphasized designing with potential users — not building first and hoping adoption follows.

“We brought together stakeholders and asked what would be a useful product,” he said. “We showed lots of iterations to Peruvian CDC officials, Brazil’s dengue program and UNICEF teams in Peru and beyond; the idea was to be very proactive in getting the opinion of people who we hoped would use this.”

Carlos Orlando Zegarra Zamalloa, Health Specialist at the UNICEF Peru Office, added, "Climate-related outbreaks like dengue and malaria are becoming more frequent and dangerous in Peru, especially for children and pregnant women. In 2025 alone, Peru reported 39,000 dengue cases, with a substantial proportion affected being children; the scale has been overwhelming the current capacity of governments and communities to respond effectively. We were therefore delighted to work together with UC San Diego and New Light Technologies to bring a range of stakeholders together to troubleshoot the problem."

DIRE is built on an ensemble machine-learning approach described in a 2024 study published in Scientific Reports, which was developed to forecast dengue incidence rates and piloted in Brazil and Peru. The approach was first conceptualized by UNICEF and the European Space Agency which developed the machine learning algorithm that DIRE implements. Expertise from UC San Diego helped translate that work into the platform that exists today. DIRE applies the conceptual framework to malaria as well, drawing on epidemiological, socio-economic, environmental and climate data sources to generate near-term projections.

McCord emphasized that the underlying predictive science has a foundation in academic literature — but the innovation is packaging that work into a tool designed for real-time decision-making.

“The disease prediction model is not new, but it’s implementing it in a way that’s trying to make it as useful for governments as possible,” he said.

DIRE is currently in a soft launch phase as the team continues to test the interface and improve data quality. For McCord and collaborators, the initial two countries and two diseases are a starting point — proof of concept for a platform that could expand to additional regions and health threats.

The project’s long-term impact will be measured by whether it becomes part of how leaders plan and respond — supported by real examples and testimonials of use in the field.

“Ultimately, success looks like governments being able to act earlier,” McCord said. “If you can see what’s likely coming—and what resources you’ll need — you can move from reacting to outbreaks to preparing for them.”

Source: University of California San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy