As the world has witnessed firsthand, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, is difficult to control because of its ability to rapidly mutate and produce many different variants. Scientists at Scripps Research have now identified antibodies that are effective against many different SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as other SARS viruses like SARS-CoV-1, the highly lethal virus that caused an outbreak in 2003. The results showed that certain animals are surprisingly more able to make these types of “pan-SARS virus” antibodies than humans, giving scientists clues as to how to make better vaccines.

The findings, published today in Science Translational Medicine, reveal the antibody structures that produce this more comprehensive immune response. They found these neutralizing antibodies recognize a viral spike region that is relatively more conserved, meaning that it is present across many different SARS viruses and is therefore less likely to mutate over time. This discovery can inform how to develop next-generation vaccines that can offer additional protection against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and other SARS-related viruses.

“If we can design vaccines that elicit the similar broad responses that we’ve seen in this study, these treatments could enable broader protection against the virus and variants of concern,” says senior author Raiees Andrabi, PhD, an investigator in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology.

In the study, rhesus macaque monkeys were immunized with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein–the outside portion on the virus that allows it to penetrate and infect host cells. Two shots were administered, resembling a similar strategy used with currently available mRNA vaccines in humans. Unlike these vaccines, however, the macaques were shown to have a broad neutralizing antibody response against the virus–including variants such as Omicron.

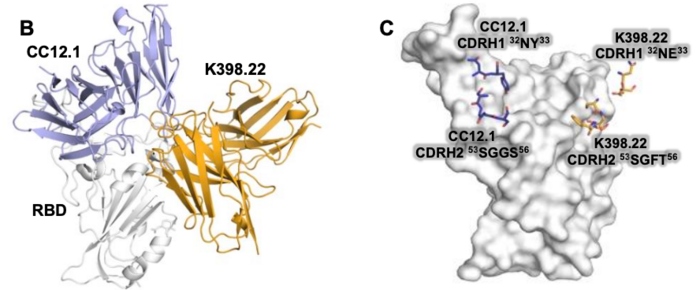

Intrigued by this stark difference, the scientists then collaborated with Ian Wilson’s lab at Scripps Research to investigate the antibody structures. They found these antibodies recognize a conserved region on the edge of the site where the spike protein binds to host cells, called the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor binding site. This is different than the region where the majority of human antibodies target, which overlaps more with the ACE2 receptor binding site and is more variable to change.

“The antibody structures reveal an important area common to multiple SARS-related viruses. This region to date has rarely been seen to be targeted by human antibodies and suggests additional strategies that can be used to coax our immune system into recognizing this particular region of the virus,” says co-senior author Ian Wilson, DPhil, the Hansen Professor of Structural Biology and chair of the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology.

It’s important to note that the macaque’s gene coding for these broad neutralizing antibodies—known as IGHV3-73—is not the same in humans. The dominant immune response in humans is related to the IGHV3-53 gene, which produces a potent but much narrower neutralizing antibody response. However, the scientists say this discovery opens the door to rationally design and engineer vaccines or vaccine-adjuvant combinations that elicit more broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 and its many variants.

“According to our study, the macaques have an antibody gene that offers them more protection against SARS viruses. This observation teaches us that studying the effect of a vaccine in monkeys can only take us so far but also reveals a new target for our vaccine efforts that we might be able to exploit by advanced protein design strategies,” adds Dennis Burton, PhD, co-senior author and chair of the Department of Immunology and Microbiology.

Because the genetics do differ, Andrabi urges that more investigation is needed—not only for identifying new strategies against SARS viruses, but also for making sure scientists are using the best translational models for their research.

In addition to Andrabi, Wilson and Burton, authors of the study, “Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-related viruses can be readily induced in rhesus macaques,” include Wan-ting He, Meng Yuan, Sean Callaghan, Rami Musharrafieh, Ge Song, Nathan Beutler, Wen-Hsin Lee, Peter Yong, Jonathan L. Torres, Panpan Zhou, Fangzhu Zhao, Xueyong Zhu, Linghang Peng, Deli Huang, Fabio Anzanello, James Ricketts, Mara Parren, Elijah Garcia, David Nemazee, Bryan Briney and Andrew B. Ward of Scripps Research; Murillo Silva and Mariane Melo of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); Melissa Ferguson and William Rinaldi of Alpha Genesis; Stephen A. Rawlings, Davey M. Smith and Yana Safonova of University of California, San Diego (UCSD); Thomas F. Rogers of Scripps Research and UCSD; Jennifer M. Dan and Alessandro Sette of UCSD and La Jolla Institute for Immunology; Zeli Zhang and Daniela Weiskopf of La Jolla Institute for Immunology; Shane Crotty of UCSD and the La Jolla Institute for Immunology; and Darrell J. Irvine of MIT and Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Source: Scripps Research