Fever, aching limbs and a runny nose – as winter returns, so too does the flu. The disease is triggered by influenza viruses, which enter our body through droplets and then infect cells.

Researchers from Switzerland and Japan have now investigated this virus in minute detail. Using a microscopy technique that they developed themselves, the scientists can zoom in on the surface of human cells in a Petri dish. For the first time, this has allowed them to observe live and in high resolution how influenza viruses enter a living cell.

Led by Yohei Yamauchi, professor of molecular medicine at ETH Zurich, the researchers were surprised by one thing in particular: the cells are not passive, simply allowing themselves to be invaded by the influenza virus. Rather, they actively attempt to capture it. “The infection of our body cells is like a dance between virus and cell,” says Yamauchi.

Of course, our cells gain no advantage from a viral infection or from actively participating in the process. The dynamic interplay takes place because the viruses commandeer an everyday cellular uptake mechanism that is essential for the cells. Specifically, this mechanism serves to channel vital substances, such as hormones, cholesterol or iron, into the cells.

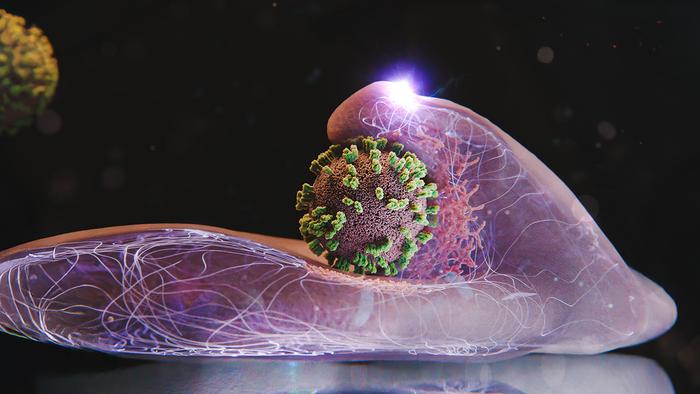

Like these substances, influenza viruses must also attach to molecules on the cell surface. The dynamics are like surfing on the surface of the cell: the virus scans the surface, attaching to a molecule here or there, until it has found an ideal entry point – one where there are many such receptor molecules located close to one another, enabling efficient uptake into the cell.

Once the cell’s receptors detect that a virus has attached itself to the membrane, a depression or pocket forms at the location in question. This depression is shaped and stabilized by a special structural protein known as clathrin. As the pocket grows, it encloses the virus, leading to the formation of a vesicle. The cell transports this vesicle into its interior, where the vesicle coating dissolves and releases the virus.

Previous studies investigating this key process used other microscopy techniques, including electron microscopy. As these techniques entailed the destruction of the cells, they could only ever provide a snapshot. Another technique that is used – known as fluorescence microscopy – only allows low spatial resolution.

The new technique, which combines atomic force microscopy (AFM) and fluorescence microscopy, is known as virus-view dual confocal and AFM (ViViD-AFM). Thanks to this method, it is now possible to follow the detailed dynamics of the virus’s entry into the cell.

Accordingly, the researchers have been able to show that the cell actively promotes virus uptake on various levels. In this way, the cell actively recruits the functionally important clathrin proteins to the point where the virus is located. The cell surface also actively captures the virus by bulging up at the point in question. These wavelike membrane movements become stronger if the virus moves away from the cell surface again.

The new technique therefore provides key insights when it comes to the development of antiviral drugs. For example, it is suitable for testing the efficacy of potential drugs in a cell culture in real time. The study authors emphasize that the technique could also be used to investigate the behavior of other viruses or even vaccines.

Reference: Yoshida A, Uekusa Y, Suzuki T, Bauer M, Sakai N, Yamauchi Y: Enhanced visualization of influenza A virus entry into living cells using virus-view atomic force microscopy. PNAS, 122: e2500660122, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2500660122

Source: ETH Zurich