A graduate student at Southern Methodist University (SMU) has developed a miniature pH sensor that can tell when food has spoiled in real time.

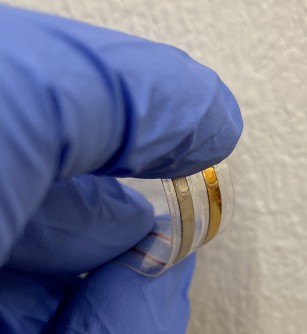

The flexible pH sensor is only 2 millimeters in length and 10 millimeters wide, making it possible to incorporate the sensor into current food packaging methods, such as plastic wrapping. Industries typically use much bulkier meters – roughly 1 inch long by 5 inches tall – to measure pH levels, so they are not suitable to be included in every package of food to monitor its freshness in real time.

“The pH sensors we developed work like a small wireless radio-frequency identification device – similar to what you find inside your luggage tag after it has been checked at airports or inside your SMU IDs. Every time a food package with our device passes a checkpoint, such as shipping logistics centers, harbors, gates or supermarkets’ entrances, they could get scanned and the data could be sent back to a server tracking their pH levels,” said Khengdauliu Chawang, PhD student at SMU’s Lyle School of Engineering and lead creator of the device. “Such configuration would allow continuous pH monitoring and accurately detect freshness limits along the entire journey -- from farms to consumers’ houses.”

Roughly 1.3 billion metric tons of food produced around the world go uneaten every year, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Nearly 40 percent of food -- approximately 130 billion meals -- is wasted in the United States, according to Feeding America estimates.

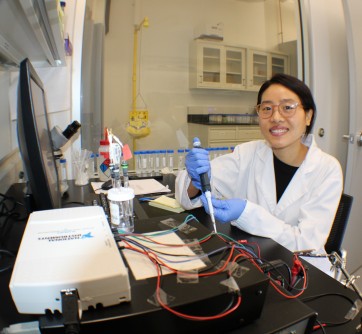

Khengdauliu Chawang

Creating the device was personal for Chawang, an electrical and computer engineering graduate student who is originally from Nagaland, a remote region in India where the population relies heavily on agricultural crops.

“Food waste in Nagaland means undernourished children and extra fieldwork for the elderly to compensate for the loss,” Chawang said. “The need to prevent food waste motivated me to think of a device that is not expensive or labor-intensive to develop, is disposable and can detect freshness levels.”

Not only does food waste contribute to food insecurity and lost profits to food manufacturers, but food wastage is also bad for the environment. Transporting all of that uneaten food in the U.S. puts about the same amount of carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere as 42 coal-fired power plants, the U.S. EPA reported in 2021.

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineer’s (IEEE) Big Ideas competition at the 2022 IEEE Sensors Conference honored Chawang with the Best Women-owned Business Pitch for her invention, which she built with the support of J.-C. Chiao, the Mary and Richard Templeton Centennial Chair and professor in the Lyle School’s Electrical and Computer Engineering Department.

Food freshness level is directly correlated to pH levels, Chawang explained. For example, food with a pH level higher than the normal range indicates spoiled food, as fungi and bacteria thrive in high-pH environments. So sudden pH changes in food storage during production and shipping can indicate possible food spoilage.

The pH level is measured by the concentration of hydrogen ions found in a substance or solution.

Because hydrogen ions are electrically-charged molecules, the electrodes within Chawang’s pH sensor can detect the electrical charge generated by the concentration of hydrogen ions inside food, converting the level to pH values using what is known as the Nernst equation.

The pH sensor has successfully been tested on food items like fish, fruits, milk and honey, Chawang said. More testing is being done.

The sensor is made with a very small amount of biocompatible materials and use printing technologies on flexible films.

“The entire process is similar to printing newspapers. The processing does not require expensive equipment or semiconductor cleanroom environment,” Professor Chiao said. “Thus, the costs are low and make the sensor disposable.”

Chiao and graduate student Chawang are investigating whether the electrode device they have developed for monitoring food could also be used to ensure reliable fermentation for cheese and wine. In addition, the same technology could have potential applications in detecting early warning signs of sepsis or wound infection when they are used on the skin, Chawang said.

Chiao, who joined the SMU faculty in 2018, is widely recognized for his research in using electromagnetic waves in medical applications including closed-loop pain management systems and gastric motility management.

Source: SMU