Smallpox was once one of humanity’s most devastating diseases, but its origin is shrouded in mystery. For years, scientific estimates of when the smallpox virus first emerged have been at odds with historical records. Now, a new study reveals that the virus dates back 2,000 years further than scientists have previously shown, verifying historical sources and confirming for the first time that the disease has plagued human societies since ancient times.

The paper appears in the journal Microbial Genomics, published by the Microbiology Society.

Smallpox, caused by the variola virus, is perhaps best known for being the only infectious human disease to be eradicated worldwide. But the disease was a major cause of death until relatively recently, killing at least 300 million people in the 20th century. This is roughly the equivalent of the population of the United States.

Until relatively recently, the earliest genetic evidence for smallpox was only from the 1600s. Then in 2020, a study that sampled skeletal and dental remains of Viking-age skeletons recovered multiple strains of variola and confirmed the virus’ existence at least another 1,000 years earlier.

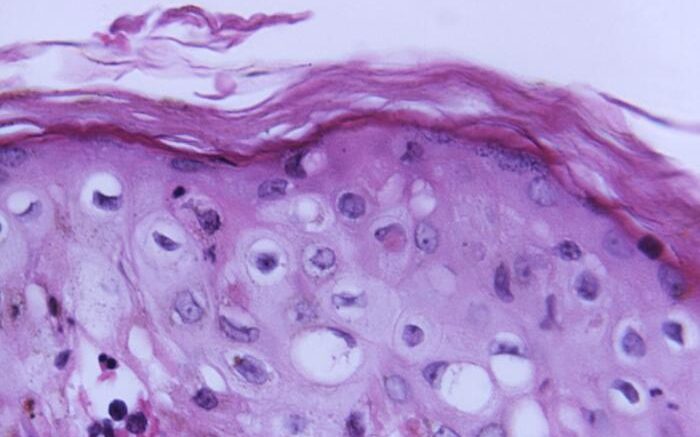

However, some historians believe that smallpox has been around since long before the Vikings. Suspicious scarring on ancient Egyptian mummies (including the Pharoah Ramses V who died in 1157 BC) leads some to believe that the history of smallpox stretches back at least 3,000 years. So far, the missing piece of scientific evidence to support this theory has remained hidden.

By comparing the genomes of modern and historic strains of variola virus, researchers at the Scientific Institute Eugenio Medea and University of Milan in Italy have traced the evolution of the virus back in time. They found that different strains of smallpox all descended from a single common ancestor and that a small fraction of the genetic components found in Viking-age genomes had persisted until the 18th century.

They also worked out an estimate for when the virus originated. In their estimate, the researchers accounted for something called the ‘time-dependent rate phenomenon’. This means that the speed of evolution depends on the length of time over which it is being measured, so viruses appear to change more quickly over a short timeframe and more slowly over a longer timeframe. The phenomenon has been well-documented in DNA viruses like variola.

Using a mathematical equation, scientists can account for the time-dependent rate phenomenon to give more accurate dates for evolutionary events, such as the appearance of a new virus. This gave the team a new estimate for the first emergence of smallpox: more than 3,800 years ago. Just as historians have long suspected.

The researchers hope these findings will settle a longstanding controversy and provide new insight into the history of one of humanity’s deadliest diseases.

“Variola virus may be much, much older than we thought,” said Dr Diego Forni, first author of the study. “This is important because it confirms the historical hypothesis than smallpox existed in ancient societies. It is also important to consider that there are some aspects in the evolution of viruses that should be accounted for when doing this type of work.”