Fecal transplantation in the intestine is an effective cure – and far superior to today’s standard treatment – for a life-threatening infection that affects between 2,500 and 3,000 people in Denmark every year. That is the conclusion of a new study conducted by researchers from Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital which has just been published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

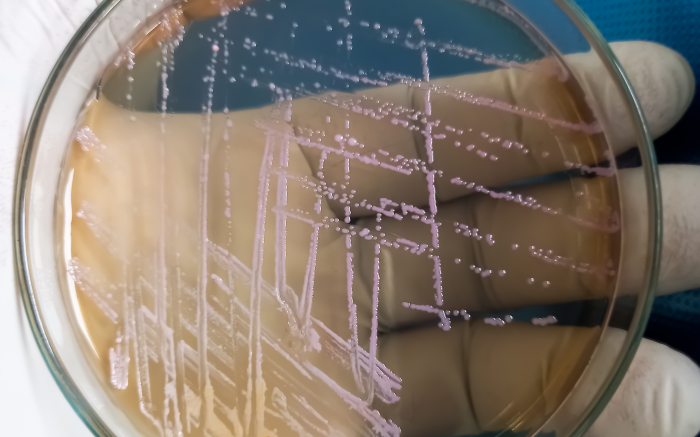

In the study, the researchers examined the ground-breaking fecal transplantation treatment for patients infected with Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile), which typically affects elderly or vulnerable patients.

The results of the study are extremely encouraging, says Simon Mark Dahl Baunwall, a PhD student at the Department of Clinical Medicine and a doctor at Aarhus University Hospital.

“Our new study shows that we can effectively cure the infection through the early use of faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) after completing the standard treatment, to prevent relapses,” he says.

The standard treatment to combat C. difficile currently consists of antibiotics, but the infection is stubborn and may return to many patients. In some cases, the infection can be fatal, because the usual treatment options are insufficient. FMT treatment is currently only available in connection with the most stubborn cases, in which three or more infections have been registered. However, the study, in which 42 patients participated, suggests that the vast majority of patients could be completely cured through the new treatment.

“We found that treatment with FMT after completing the standard treatment cured 19 out of 21 patients, whereas only seven out of 21 treated with a placebo or another antibiotic were cured. In other words, the probability of curing the infection is three times greater after treatment with FMT than with our current standard treatment alone,” explains Baunwall.

FMT treatment is performed by transferring healthy donor feces, which contain a complete microbial intestinal ecosystem, to patients with disorders in their intestinal microbiota.

In the study, the effect of the treatment was so significant that the project had to be stopped for ethical reasons.

“In rare cases, it can happen that you discover that the treatment you are investigating is so effective that it is ethically indefensible to continue,” says Baunwall.

“Our study is one example, in that the new FMT treatment is so much better than the standard treatment with antibiotics that it would be unethical to continue, because the patients in the control group would risk not receiving the FMT treatment.”

Denmark is the country in Europe that is most advanced with the roll-out of the treatment to the patient group in question. However, a survey last year revealed that only 25 per cent of the patients who could benefit from FMT treatment were offered it. In Europe as a whole, the figure is just 1 in 10.

There are also many indications that FMT is not just an effective treatment for patients with C. difficile: the treatment is also being tested on a wide range of other diseases where disturbances in the intestinal microbiota may be a triggering factor.

“At the moment, many studies of FMT treatment for various diseases are being carried out worldwide, with the most promising of these indicating beneficial effects in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and multi-resistant bacteria,” says Baunwall.