Following an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) in a flock of around 125 Muscovy ducks in a domestic setting in South West England on Dec. 22, 2021, the virus was later also confirmed in the asymptomatic flock owner.

While transmission of avian influenza viruses from birds to humans is generally rare, these viruses may adapt and gain the ability to also spread from person to person. Timely identification of human infection is thus vital to prevent further spread.

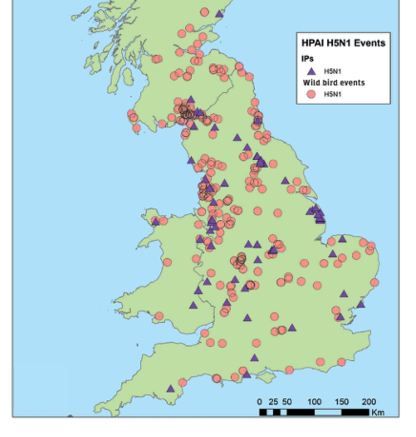

In their rapid communication, Oliver et al. describe the clinical epidemiological and virological aspects of this first human case of avian influenza A(H5N1) in Europe. In Great Britain, the autumn/winter 2021/22 season has seen the largest ever number of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) wild bird detections and poultry outbreaks since 2003.

Influenza A(H5N1) was confirmed in 19 out of 20 sampled live birds from the flock on 22 December 2021. The flock owner had been in close contact with the infected birds without any personal protective equipment but remained asymptomatic during an extended treatment course of antiviral medication (oseltamivir) for 10 days until two consecutive Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were negative. During that time, the health authorities initiated comprehensive contact tracing among 11 human contacts. Among those contacts no additional primary cases or secondary transmissions were observed.

During the investigation, the sequences of all gene segments from the human virus strain were compared with those of the duck virus and the analysis confirmed that the H5N1 in the flock owner’s respiratory material was identical in all segments to the avian sequence, apart from four nucleotide (nt) mutations.

According to the authors, "the circumstances regarding exposure to birds were unusual, with a high degree of close contact with a large number of infected birds and a virus-contaminated enclosed domestic environment which resulted in infection. The spill-over infection to the human contact did not lead to any detected genetic changes in the virus that might be associated with increased zoonotic risk. This case demonstrates the increased risk posed by this kind of close contact but does not change the overall assessment that the risk to the general public from avian influenza virus remains very low."