Monkeypox can sometimes lead to neurological complications such as encephalitis (brain inflammation), confusion or seizures, finds a new review of evidence led by a University College Longon (UCL) researcher.

Several studies incorporated in the systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence, published in eClinicalMedicine, also found that muscle aches, fatigue, headache, anxiety and depression were all relatively common among monkeypox patients.

Across the studies with relevant evidence, 2%-3% of patients had severe complications such as seizure or encephalitis, although those studies mainly involved hospitalized patients from previous years. The researchers say there is not yet enough evidence to estimate neurological complication prevalence in the current outbreak.

The team led by researchers at UCL, Barts Health NHS Trust, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, and King's College London, looked for any studies reporting neurological or psychiatric symptoms of monkeypox that had been reported up until May 2022, before the outbreak spread globally.

Lead author Dr. Jonathan Rogers (UCL Institute of Mental Health, UCL Psychiatry, and South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust) said, “We found that severe neurological complications such as encephalitis and seizures, while rare, have been seen in enough monkeypox cases to warrant concern, so our study highlights a need for further investigation. There is also evidence that mood disorders such as depression and anxiety are relatively common for people with monkeypox.”

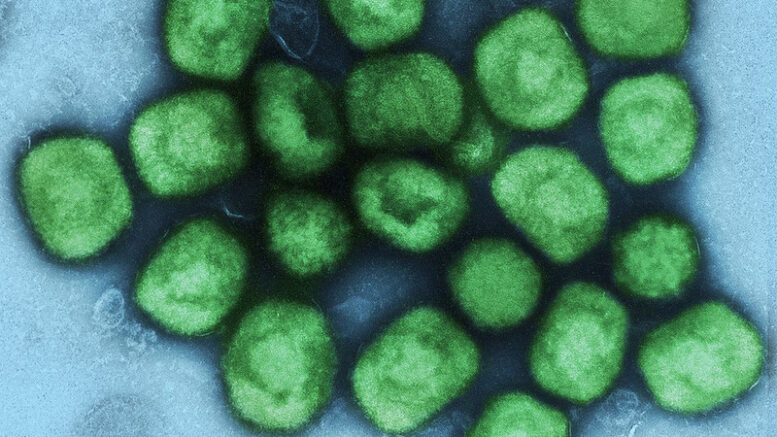

Monkeypox primarily causes skin lesions and fever, and can be fatal, although in the current outbreak, substantially fewer than one in 1,000 confirmed cases have resulted in death. Although it has been endemic in parts of Central and West Africa for decades, with sporadic outbreaks elsewhere, 2022 has been the first time the virus has spread globally, attracting increased attention to an infectious disease that was previously relatively neglected.

The review incorporated 19 studies, with a total of 1,512 participants (1,031 of whom had a confirmed infection), in the US, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, and the UK.

By pooling data from across a sub-set of studies with relevant evidence, the researchers estimated that 2.7% of monkeypox patients experienced at least one seizure, 2.4% experienced confusion, and 2.0% had encephalitis, a serious condition of brain inflammation that can lead to long-term disability. There was very limited evidence for the prevalence of such symptoms, as the review only identified two cases of seizures, five cases of encephalitis and six cases of confusion (although other preliminary research has identified other cases), so larger studies are needed to better ascertain prevalence. The researchers say that further study is also needed to determine how monkeypox can impact the brain.

While the researchers were not able to pool data for psychosocial symptoms due to incomplete evidence, in some studies at least half of patients experienced at least one of myalgia (muscle aches), fatigue, headache, anxiety or depression. The researchers note that monkeypox may cause higher rates of mental ill health than other illnesses due to the presence of potentially disfiguring lesions, while there may also be stigma linked to how transmission is typically from close physical or sexual contact.

The studies reviewed did not have enough long-term follow-up with patients to know whether any of the symptoms last substantially longer than the acute phase of the illness. The researchers also caution that most cases in this review were hospitalised patients, and so the studied symptoms might not be as common in people with more mild cases.

Co-author Dr. James Badenoch (Barts Health NHS Trust) said, “As there is still limited evidence into neurological and psychiatric symptoms in the current monkeypox outbreak, there is a need to set up coordinated surveillance for such symptoms. We suggest that clinicians should be watchful of psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety and ensure that patients have access to psychological and psychiatric care if needed.”

Source: University College London