In Brazil, a group of researchers supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) created mutant forms of Salmonella to understand the mechanisms that favor colonization of the intestinal tract of chickens by these pathogenic bacteria and find better ways to combat the infection they cause.

An article on the study is published in the journal Scientific Reports. In it, the researchers note that, contrary to expectations, the mutant strains caused more severe infections than wild-type bacteria.

In the mutant strains, the genes ttrA and pduA were deleted. In previous research using mice, both genes had been shown to account for the ability of Salmonella to survive in an environment without oxygen, favoring intestinal colonization and dissemination in a production environment.

“This would confer an advantage in competition with other microorganisms that also inhabit the intestinal tract,” said Julia Cabrera, first author of the article. She had a technical training scholarship from FAPESP and is currently conducting doctoral research at São Paulo State University’s School of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences (FCAV-UNESP) in Jaboticabal.

“Salmonella’s genetic apparatus is sufficient to enable it to change behavior in response to not only hosts [commercial poultry] but also other bacteria that compete with it in the same environment. When these two genes were deleted, it found other survival mechanisms and became even more pathogenic to the birds,” said Mauro Saraiva, second author of the article and responsible for leading the study during a postdoctoral fellowship at FCAV-UNESP.

The findings reinforce the importance of taking animal health measures as soon as chicks are hatched and until slaughter, as well as care during meat transportation and conservation. A vaccine to prevent intestinal colonization of poultry by strains of Salmonella responsible for food-borne outbreaks of human salmonellosis lies beyond the horizon for now.

The study is part of a project supported by FAPESP and led by Angelo Berchieri Jr., a professor at FCAV-UNESP.

According to Berchieri Jr., few food-borne human infections have been detected in Brazil, but consumers should not neglect proper food conservation and hygiene. “The Salmonella serotypes known to cause food-borne diseases don’t always make a person sick. Although there are other important routes for these bacteria to be introduced into poultry farms, the greatest danger occurs when very young chicks are exposed, as their immune system isn’t fully formed,” he said.

In these cases, fecal excretion lasts longer and causes more extensive contamination of the chicken shed. As a result, more infected birds are transported to the slaughterhouse. Most contamination of carcasses (chickens ready for sale) occurs during this stage.

In the study, laying hens and chicks of various ages were first infected with the serotypes of Salmonella enterica most frequently found in Brazil, Enteritidis and Typhimurium, using mutant strains with ttrA and pduA inactivated in the laboratory. The infections were compared with those caused by wild-type strains of the same serotypes, in which all genes were functional.

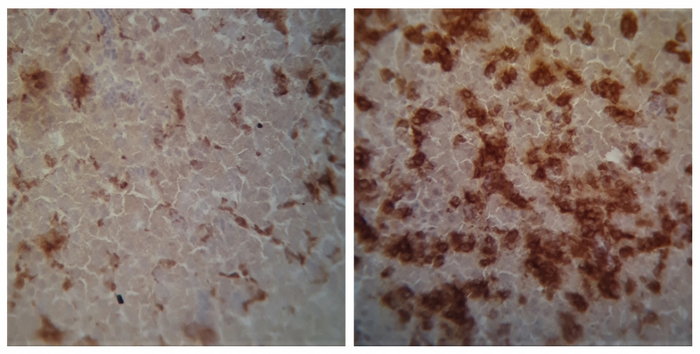

The cellular immune response was measured using immunochemistry methods, which are based on antigen-antibody reactions and staining of compounds formed in infected tissue. The larger the area stained, the more exacerbated the organism’s cellular response to infection. The researchers analyzed different parts of the intestinal tract (cecal tonsils, cecum and ileum), as well as the liver.

Mutant strains of Enteritidis caused a more pronounced cellular immune response than wild-type strains, except in laying hens. Both mutant and wild-type Typhimurium caused a similar response.

In all lineages studied, tissue infected by Salmonella was infiltrated by significant quantities of macrophages, immune cells that attack bacteria and other pathogens.

“The next step will entail real-time PCR testing to understand which molecules are involved in this more exacerbated immune response in birds infected by mutant strains,” Saraiva said.

Source: São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)