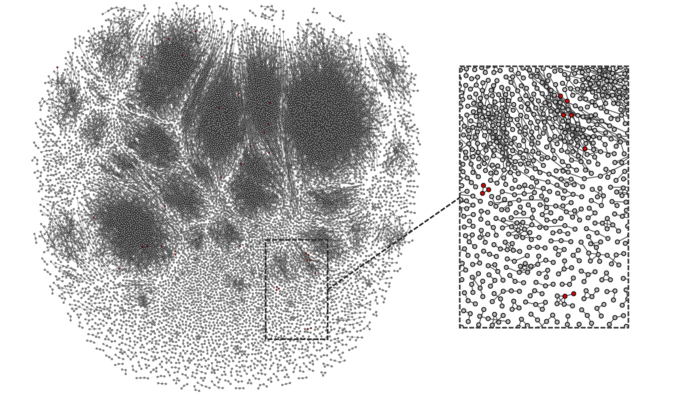

This image provides an overview of the T-cell response in a study participant. Shown in red are the vaccine-specific T cells present following vaccination. Courtesy of Elias, Meysman, Bartholomeus et al.

Researchers have shown how pre-existing immune cells in the blood may help individuals develop rapid and strong protection against hepatitis B infection following vaccination.

Their methods, described today in eLife, may lead to new ways for scientists and clinicians to predict which individuals will be protected by vaccination against hepatitis B infection, and who may have a delayed or inadequate immune response. They may also help them better understand how individuals develop natural immunity to pathogens or immunity following vaccination.

Immune cells called CD4 T cells help the body recognize pathogens. They also recognize vaccine antigens that help the body identify and develop immunity to the pathogens. Once a CD4 T cell recognizes a pathogen or a vaccine antigen, it develops into a memory cell ready to defend the body quickly against future infections.

“Some people also have pre-existing memory CD4 T cells that recognize pathogens or vaccine antigens that they haven’t even been exposed to before. We wanted to find out if having pre-existing memory CD4 T cells that recognize the hepatitis B vaccine surface antigen helps individuals develop immunity after vaccination,” explains George Elias, who worked on the study while he was a PhD student at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute, University of Antwerp, Belgium. Elias is a co-first author of the study alongside Pieter Meysman and Esther Bartholomeus (University of Antwerp).

To answer this question, the team recruited 34 people who had never been exposed to hepatitis B or vaccinated against it. They collected blood samples from these individuals before and after they were given two doses of the hepatitis B vaccine. They then used next-generation sequencing and machine learning methods to analyze the memory CD4 T cells in these individuals before vaccination and at three time points following vaccination.

Their analysis revealed that participants with a higher number of pre-existing memory CD4 T cells that recognized the vaccine antigen developed immunity more quickly and produced more antibodies following vaccination. They also showed that using immunosequencing to analyze the participants’ pre-existing memory CD4 T cells could predict whether they would rapidly produce strong immunity after hepatitis B vaccination.

The authors say that the ability of CD4 T cells to recognize multiple antigens may explain why even people who have never been exposed to hepatitis B or its vaccine have pre-existing memory cells that recognize the virus. These memory cells may have been generated in response to environmental exposures or to microbes that live in the human body, but more research is needed to better understand their origins.

“Our analysis has uncovered a role for pre-existing memory CD4 T cells in mounting a quick and powerful immune response to the hepatitis B vaccine,” says Benson Ogunjimi, co-founder and biomedical coordinator of the Antwerp Unit for Data Analysis and Computation in Immunology and Sequencing (AUDACIS), and a co-senior author of the study alongside Viggo Van Tendeloo and Kris Laukens (AUDACIS). “We’ve shown that pre-existing memory CD4 T cells could affect the outcome of vaccination, which may have significant implications for immunity and vaccine development efforts.”

Ogunjimi and his co-authors have launched a company based on the next-generation sequencing methods described in their work. ImmuneWatch works to provide in-depth sequencing and analysis of the human T-cell response, and aims to transform this data into clinically actionable insights for the development of improved vaccines and immune therapies.

Source: University of Antwerp