During the COVID-19 pandemic, the world became aware of the value of using sewage analyses to monitor disease development in an area. However, at DTU National Food Institute, a group of researchers has been using sewage monitoring from throughout the world since 2016 as an effective and inexpensive tool for monitoring infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance.

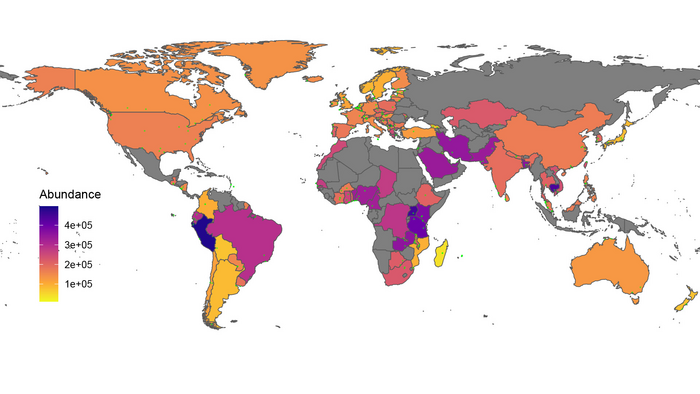

By analyzing sewage samples received by DTU from 243 cities in 101 countries between 2016 and 2019, the researchers have now mapped where in the world the occurrence of resistance genes is highest, how the genes are located, and in which types of bacteria they are found.

The results from the new metagenomic study—which have just been published in Nature Communications—have surprised the researchers. In fact, the study shows that the genes have appeared in many different genetic contexts and bacterial types, indicating greater transmission than the researchers had expected.

“We’ve found similar resistance genes in highly different bacterial types. We find it worrying when genes can pass from a very broad group of bacteria to a completely different group with which there is no resemblance. It’s rare for these gene transmissions to occur over such long distances. It’s a bit like very different animal species producing offspring,” explains assistant professor Patrick Munk.

If the genes are in bacteria that don’t usually make people sick—such as lactic acid bacteria—it’s of less concern. However, if the resistance genes find their way into bacteria that are important to human health—such as salmonella—it’s a completely different story.

"This makes it much more likely that the bacteria will actually kill people—for example in a hospital—because no treatment is available,” emphasizes Munk.

In different places in Sub-Saharan Africa, the researchers have found the same resistance gene in a number of different bacteria.

“We interpret this to mean that we may be quite close to a transmission hotspot, where there is a gene transmission from one to another to a third bacterium. That’s why we’re seeing the gene in so many different contexts precisely there,” Munk explains.

He adds that many of the surprising transmissions appear to occur in the Sub-Saharan Africa. These are also countries with the least developed programmes for monitoring resistance, which means that there is very little data on the resistance situation.

“We risk overlooking important trends because we don’t have data,” he suggests, stressing that solid data is exactly what is needed to develop effective strategies for combating resistance. Right now, we have huge knowledge about how resistance behaves in the West and—based on that knowledge—we plan how to combat resistance. It now turns out that if we look at some new locations, the resistance genes may behave very differently—presumably because they have more favourable transmission conditions. Therefore, the way in which you combat resistance must also be adjusted and tailored to the local conditions.”

The global sewage project—which is supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the VEO research project—concludes in 2023. The researchers find that it has proved to be a good supplement to existing monitoring initiatives, which mainly operate at national or regional level and measure resistance in bacteria from sick people.

They therefore hope that a successor to the project will appear, so that the world can continue to benefit from the important knowledge generated by the monitoring programme. This also applies to countries that have solid monitoring programmes and control strategies in place.

“There are many analogies with climate change, where what happens on the other side of the globe isn’t unimportant to you. One day or another, the problem will come back to bite us, as we’ve seen time and again,” Munk stresses.