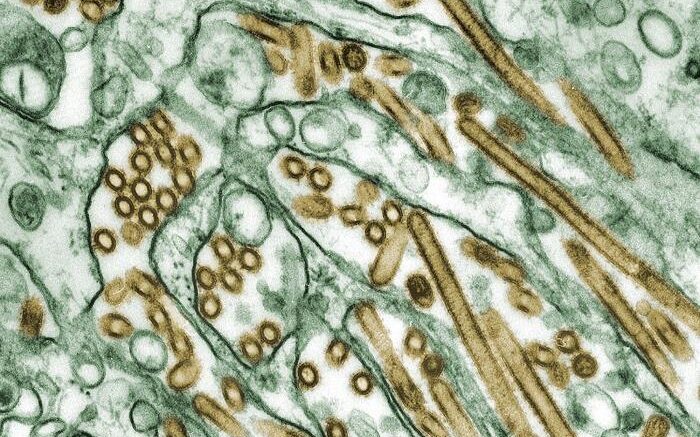

With the recent outbreaks identified in Canada and the United States, H5N1 – a strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIv) – is rapidly becoming a global concern. The virus has already caused widespread outbreaks throughout Asia, Africa and Europe, resulting in millions of deaths in poultry and wild birds.

In a new Perspective in Science, Michelle Wille and Ian Barr discuss the factors that have led to global H5N1 HPAIv outbreaks, the consequences of this spread, and what can be done to curb it.

“The ongoing 2021-2022 wave of avian influenza H5N1 is unprecedented in its rapid spread and extremely high frequency of outbreaks in poultry and wild birds, and is a continuing potential threat to humans,” the authors write.

Since 2020, highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses have spread across the globe. Although such viruses often emerge in high-density poultry production systems, they can also infect wild migratory birds. One particular lineage, H5N1, is responsible for the most recent wave of infections, which have been identified across Eurasia and in Africa and North America. The virus can be deadly in bird populations and has already caused mass mortality events in wild birds, threatening whole populations, particularly those already endangered. What’s more, the virus has already had a substantial impact on poultry production. In 2020 and 2021 alone, roughly 15 million poultry have been culled or have died because of HPAIv infections.

Perhaps most concerning is the virus’s ability to infect humans. Although bird-to-human infections have been rare in the last two decades, and sustained human-to-human transmission has yet to be documented, highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses pose a potential pandemic risk. Further adaption in this current virus could increase its ability to transmit between humans efficiently.

To avoid this, Wille and Barr argue that international health and agricultural organizations need to take each avian influenza outbreak seriously, particularly in settings where humans are involved. Among other measures, they call for continued investment in surveillance of wild birds and poultry and of humans at the human-poultry interface. They note that measures such as reduction of flock size and density and avoidance of poultry production in waterbird-rich areas have been proposed to prevent spillovers of HPAIv into wild birds.