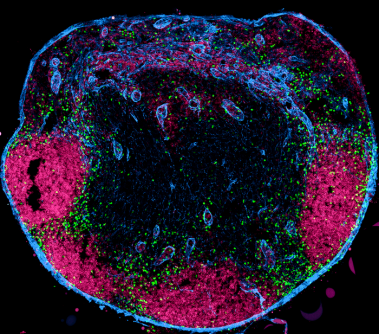

The human body contains 600 to 800 lymph nodes, which are specialized organs that trigger immune responses. To be informed about infections in the body, lymph nodes are connected to the individual organs via lymph vessels. From the organs, the lymph vessels transport fluids and special immune cells to the lymph nodes. These immune cells are called dendritic cells; they carry information from the organs into the lymph nodes and pass it on to other immune cells there.

Now it is clear: the dendritic cells are not solely responsible for this important flow of information. A research team led by immunologist professor Wolfgang Kastenmüller from Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, has discovered that so-called unconventional T cells also continuously migrate from the tissue into the lymph nodes and influence the immune responses there.

This discovery has consequences – for vaccination strategies as well as for immunotherapies against cancer.

"Each tissue in our body has different subtypes of unconventional T cells," explains Kastenmüller. "Since these cells each migrate to the nearest lymph node, the individual lymph nodes also differ in the composition of the T cells. And that has a direct effect on the immune responses of the individual lymph nodes."

For example, a lymph node that has been informed about an infection in the lungs triggers a different immune response than a lymph node that receives its information from the intestine or from the skin.

A vaccination administered into the skin or muscle, for example, always addresses lymph nodes that are connected to the skin. However, the vaccine may be much more effective if it is administered near other lymph nodes. This consideration also applies to immunotherapies against cancer.

"That is why we want to investigate next whether we can use the difference in lymph nodes to make vaccinations more efficient or to improve immunotherapies against cancer," says the JMU professor. Another interesting question is whether the differences in the lymph nodes can be actively influenced. And it is to be clarified what significance the new findings have with regard to the development of autoimmune diseases and cancer.

The results of the researchers have been published in the journal Immunity. Marco Ataide, Paulina Cruz de Casas and Konrad Knöpper, all from Kastenmüller's team at the JMU Chair of Systems Immunology I, were significantly involved in the work. Researchers from the Würzburg Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI), the JMU Institute for Molecular Infection Biology (IMIB), the Centre d'Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy (CIML) and the Medical Clinic II of the Würzburg University Hospital also participated.

Source: University of Würzburg