Parents may not always turn to health professionals for vaccine advice – and a small subset could even be avoiding the conversation – a new national poll suggests.

One in seven parents haven’t had any discussions about vaccines with their child’s regular provider over the last two years, according to the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at University of Michigan Health.

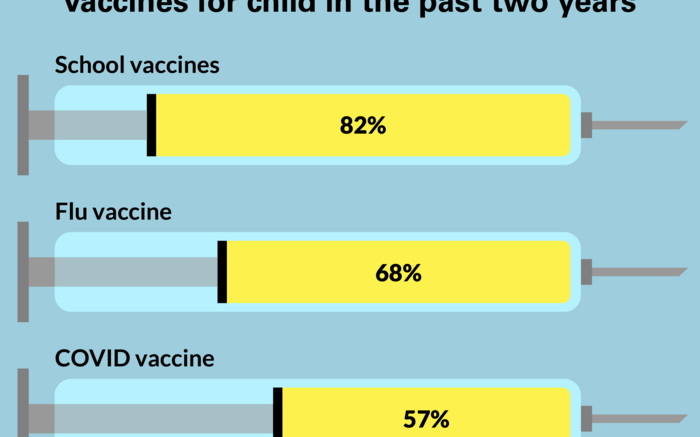

And while 80% of parents have talked about vaccines required for school with their child’s provider, fewer have discussed immunizations for influenza (68%) and COVID-19 (57%).

“Historically, parents have relied on their child’s pediatrician or other primary care provider to guide them in decisions about their child’s health, including recommendations about vaccines,” said Mott Poll co-director Sarah Clark, MPH. “With a new vaccine like COVID, we would expect parents to have a lot of questions and concerns, and we would expect parents to turn to that trusted primary care provider who has guided them through other vaccine decisions for their child. The lower rates of discussions for the COVID vaccine may suggest a downturn in the role of the primary care provider as the go-to source on this topic.”

The nationally representative report is based on responses from 1,483 parents with at least one child aged 6-18.

Vaccines are a frequent topic of discussion during children’s check-ups, Clark says, as parents often have questions about vaccine timing, benefits, risks and side effects.

“Different vaccines are recommended for different age groups and as new vaccines are developed, well visits provide an important opportunity to ask questions about them,” Clark said.

“During the pandemic we saw a lot of misinformation and division over vaccines, as well as disruptions in care because of COVID precautions. This may have affected how often parents were talking with their child’s regular provider. Without that trusted source of vaccine information and guidance, families may turn to other sources that may be less accurate.”

Parents who have talked with their child’s regular doctor about flu or COVID vaccines report positive experiences. The majority polled described providers as being open to their questions and concerns, and more than 70% said they learned information that was helpful to their decision making.

Those who discussed vaccines with their child’s regular provider were also more likely to get their child vaccinated.

However, a quarter of parents polled also described problems getting vaccines for their child over the past two years, such as having to go to another location or problems scheduling appointments.

Clark notes some of these challenges could be related to pandemic precautions, including limited in-person visits, when pediatricians may have felt more rushed during check-ups and not covered all recommended topics, including vaccines.

Providers may also be less likely to discuss vaccines that are not offered at their own site. While school vaccines are often in stock and ready to be administered at any time, flu and COVID shots mat not be consistently available in child health practices.

“This situation disrupts the parent-provider discussion around those vaccines,” Clark said. “Even when parents bring the child in for a visit, they may be told that they need to go elsewhere to get flu and COVID vaccines, requiring extra time and hassle for families.”

Among the most concerning findings: a subset of parents who opt out of any vaccines for their child may be avoiding crucial health conversations with health professionals.

Six percent of parents say their child does not get any vaccines. Among this group, 43% report no vaccine discussions with any healthcare provider in the past two years.

Another 3% of parents say they delayed or skipped a healthcare visit for their child to avoid talking about vaccines. While that number seems small, “3% translates to a lot of children across America,” Clark notes.

“Avoiding conversations about vaccines with a child’s health provider prevents caretakers from learning about and considering new information that might influence their decision,” Clark said.

“When parents delay or skip visits altogether, they are not prioritizing their child’s well-being,” she added. “Children won’t receive screening for medical or mental health problems, and parents will not receive information or guidance about how to keep their child healthy and safe.”